A Guide to Clifford House in the 1950’s

Alan Tritton

Plan of Clifford House prepared by J.J. Cheal in 1950.

You entered the hut by the outer porch which led straight into the coal hole – not a very impressive entrance but then we only had visitors once or twice a year. Then there was the inner porch with hooks for our anoraks, wind proofs, sledging gloves etc. The third door led into the hut proper.

On the left was the bunkroom where we lived, slept and worked. We had a stove there which was never let out on fear of instant death, a survey desk, a gramophone and a small polar library.

Straight ahead was the radio room with its transmitters and receivers. To the right of the radio room was the met office with all its instruments and opposite that was the kitchen, which had a wonderful Esse cooker which never went out and next to it the water tank which had to be laboriously filled up daily with blocks of snow (and a block of snow makes very little water when melted).

Continuing to the right we find on the left a passage where we kept a lot of stores. (The bulk of the stores were for safety reasons – mainly fire – kept in the Nissen hut.) Going on further there was a laboratory on the left, adjacent to that was a greenhouse but that blew away in a blizzard, and on the right a darkroom and a workshop. And that was that.

Outside there was a small shed housing the diesel engine which had to be cranked up every morning, sometimes with difficulty. There was an outside toilet built to the specification of Surgeon – Commander Bingham and therefore always called the ‘Bingham Bog’ with the admonitory sign “no micturition before defaecation”. This was actually extremely important because the biscuit tin underneath the bog seat became unbearably heavy if the practice was not observed. It had to be carried 100 yards or so down to the tide-crack and emptied.

Further Clifford House Era Snippets

Alan Tritton

The daily and, for that matter, nocturnal regime was very demanding. For the duty meteorologist the day started at 6 a.m. when he undertook his first synoptic observations of the day. These continued throughout the day every three hours until 3 a.m. the following morning, i.e. a 21-hour day, when he was allowed to sleep until mid-day. Wireless transmissions were carried out regularly and we were in frequent contact not only with the other FIDS stations but also Stanley and sometimes Heard and Macquarie Islands. We were also able to communicate directly with the Admiralty in London and they with us, using the secret four-figure naval code, which was a devil to decode. The Admiralty, of course, were primarily interested in the movements of Argentinian naval ships and more about that later.

We also took it in turns to cook – one week on and four weeks off. We had to cook three meals a day, trying to make them as varied as possible, and every other day, we had to bake bread – not as simple as it sounds in a cold draughty hut. I even made hot-cross buns and puff pastry. We had brought down from Stanley a number of mutton carcasses, which we deposited in a crevasse in a glacier – a useful deep freeze – and during the season we ate penguins – breasts only – and occasionally seal meat, of which the best by far was leopard seal. We got used to cooking penguins. Penguin meat is slightly fishy and therefore needs a lot of onion, herbs, tomatoes, Lea & Perrins etc. to disguise it. Having done this remedial work, it is usually very tasty. A point to note is that penguin meat goes black when you cook it. Don’t be put off. The best seal meat I ever had was the liver of a leopard seal. The meat is excellent but the liver is superb with fried dried onions and tinned bacon.

To all intents and purposes, although we washed our clothes, we did not wash ourselves. I think that the main reason for this was the sheer fatigue of cutting snowblock after snowblock, hauling them up to the hut and hoisting them into our hot water tank. We never shaved, but once a month I did treat myself to a bath in an old whale oil barrel, in which it was possible to immerse oneself – just. However, this process did, of course, entail a huge number of snow-blocks. This monthly immersion in the barrel was of enormous efficacy and to emerge clean and soaped was always a great morale booster. After one had dried and dressed, the barrel and its contents had to be manoeuvred through our three doors onto the pee glacier.

In 1953, the Argentinians constructed a small station on Deception Island but they were ejected by two Falkland Island policemen with Royal Marines in support. As a result I received my first coded message from the Admiralty. This took me a long time to decode: ‘Expect reprisals as a result of the Royal Marines action at Deception Island’. I radioed back in code asking what I should do if an Argentinian ship appeared in the Bay. The answer to that was that I was to deliver a formal protest as Magistrate of the South Orkneys that the Captain of the Argentinian ship was infringing Her Britannic Majesty’s Sovereign waters and must depart immediately. I radioed back that I thought it would be difficult as I had only a leaking old pram dinghy and one 12 bore shot-gun – my own. I was told to do my best in the circumstances.

An Argentinian frigate did appear. I launched the pram and got the outboard engine working to deliver my Protest. But, as forecast, the pram started to sink about halfway out to the ship, the outboard engine spluttered and stopped. We were left rowing along, with two men baling. Eventually, we were rescued by the Argentinians. We climbed up the rigging ropes, dirty, unshaven, stinking of seal meat. Once on the deck I demanded to see the Captain who, as it happens, had been at Dartmouth, and I delivered to him my formal letter of Protest and advised him that he had to depart forthwith. He then delivered his formal letter of Protest, advising me that I was infringing Argentine sovereign territory and that I had to depart. Having exchanged protests, he invited us in for a drink. It suddenly became all very enjoyable. After several hours of toasting each other’s health, we departed and went back to base – our pram towed by the Argentinian motorboat. It was, of course, both farcical and ridiculous but slightly uncomfortable at the same time. It would have been perfectly possible for them to have ejected us just as we had ejected them from Deception Island.

|

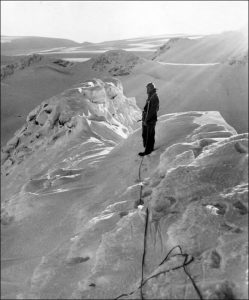

“At the top I experienced some sort of very spiritual emotion. It was a glorious day, a bright blue clear sky, not a breath of wind, no noise, no birds, no animals, nothing and stretching all around us was this most beautiful panorama of mountains, islands, glaciers, ice-cliffs, ice-caps, pack-ice, icebergs, all frozen into an astonishing immobility and stretching for what seemed hundreds of miles. It was not only beautiful it was also sublime.”

Alan Tritton. |

Extracts from the Concise Account of Signy Island Base H

Edited by D. Rootes

A few days after the relief of the base in 1950, a tremendous gale blew up and a recorded gust of 105 mph damaged the Nissen hut doors. The first dogs to be used on Signy were landed from RRS John Biscoe in February that year and the first pups, four bitches and five dogs, were born in early April. [Does anyone have stories of the Signy dogs? – Ed]. An important landmark for Signy Island history was the the opening of the first efficient darkroom in Clifford House on 2nd July 1950, thus inaugurating the great Fid tradition of photography.

During the winter, depot-laying journeys were undertaken, including one to Shingle Cove to prepare for a topographical and geological survey of Coronation in August. After nearly a month’s work the party returned to Signy, having travelled more than 200 miles. In 1952 Wave Peak was climbed for the first time by F. Johnston.

The whaling station continued to provide building materials and these were used to build a jetty ahead of the visit of the Governor, Sir Miles Clifford in November 1953. However the jetty was later carried away by ice during a gale.

The old Nissen Hut was now in a deplorable condition and various additions to Clifford House had produced an architectural dog’s dinner, not aided by the differential settling of the various parts. As a result a search was made for an alternative site for a new hut. The site of the whaling station was considered most suitable, owing to it’s sheltered position and proximity to a good landing beach.

Memories of Building Tonsberg House

Peter Cordall

If you stood outside the front door of Clifford House as if to go in, the back door was slightly behind your right shoulder. This would have made the building of further extensions very difficult and we thought that this was the real reason for replacing the hut, rather than the official stuff about differential subsidence. Whatever the reason, in February 1955 John Biscoe arrived with the makings of the new hut and we were left to get on with building it. Ron, a former builder in the East End (and a former Royal Marine sergeant), was in charge of the job. His highly skilled construction team consisted of an airman, a sailor, two office wallahs, a zoologist and a mechanic.

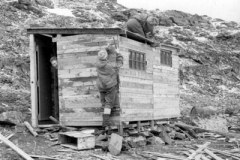

Left – Tonsberg foundations; Right: Erecting Tonsberg House

For the first few days we had plenty of labour. Concrete mixing and pier-building went pretty well and a lot of heavy work was done before the ship left. The wooden parts of the hut were all numbered and theory suggested that if you started with piece no. 1, nailed piece no. 2 to it, and so on, you would finish up with a hut. Like many Fids’ theories this was not altogether infallible, but it served as a rough guide.

Work went on through March, sometimes in awful weather. A tongue-and-groove floor, about 25 metres by 8 metres, appeared on the piers, followed by frames of 4×2 for the walls. The loft floor, another vast expanse of T&G, supported the frames and trusses for the roof. Nothing was owed to high technology, the same methods would have worked equally well for a garden shed at home.

Building dominates my diary entries for the time:

1 March, Finished the loft floor’. A few days later: ‘Half the base are walking wounded, Jim with a sprained wrist, Harry with a nail hole in his foot, Alan with back pains, me with a finger nail hanging off, all connected with building’.

8 March: ‘Roof boarding finished at 1100. Lance and I have become the East Wall gang’. More complex this, with windows to be fitted in the right places. We were working inside as well by now.

Notes in my diary mention about painting and fitting skirtings which was slowed down by Ron’s insistence on mitred corners. The last rolls of roofing felt were fixed on 22 March, fortunately a day with no wind.

Normal base routine was going on at the same time, as well as the jobs which just cropped up: a broken dog span one night, the jetty to be rebuilt after it was destroyed in a gale. Boxes and boxes of stores and gear were moved down from Clifford House, some with obvious contents, others holding long forgotten collections of things kept because they might come in useful.

HMS Burghead Bay visited bringing the Governor on his annual jaunt around the bases. The captain sent a working party ashore to move some of the old whaling station digesters for us. A day of shouting and heaving and small explosions, but not a great success overall. I think it was for this occasion that John’s newly painted Tønsberg House sign with the elephant seals and the motto was put up. The motto had first appeared, piped in icing, on the side of the previous year’s Midwinter cake.

21 April,1955 was the day set aside for the big move. The old Greenland sledge came into its own that day. First load downhill over the rocks was Lofty’s big transmitter. While people struggled with that, Harry and I started to dismantle the Esse; the top, the back, one side and an improbable amount of rock wool were removed easily enough, but the rest of it insisted on staying together in one big, heavy piece. It had to be dragged across the kitchen by main force, only to find that it would not fit through the passage. We modified the hut with sledge hammer and saw and eventually manhandled the stove bits down to the new kitchen, overturning only once on the rocks, small cracks only. Miraculously it went back together beautifully and we had the fire lit again by 9 pm. We were in!

It was certainly more spacious, more sheltered and warmer than the old hut, if a good deal further from the met screen. Clifford House lived on as the first boathouse. On the wall in the back room at home I have a piece of T&G, complete with Crown Agents stamp and manifest number, from the loft floor, as a reminder of those times.

Poems

A.A. Smith

SignyOn darkly massed rocky crags, ‘neath the island’s summer mank, quietly sit blue-eyed shags, above seals on stony bank. Seaweed heaves on ocean’s breast, close by Gentoo penguins nest.

Pack-ice from the Weddell Sea Has come, birds and seals have fled. Ice as far as ice can see, winter darkness lies ahead. The ice bound island, lifeless; with the elements, strifeless.

Starkly white the snow and rime, the old ice, translucent, blue. With clear skies and weather fine Wint’ry sun bodes change anew. Signy Island cold, serene, soon will hear the spring storms scream.

Gales have scattered the ice-field; Beneath dark clouds birds return To nest sites again revealed, Court and copulate in return. On stones penguins incubate And bull seals impregnate.

Short days presage winter. Instincts forbid them linger. |

The FöhnThe north wind traverses the ocean taking up vapour in its progress, and forming cloud by convective motion. Into a dense sheet the clouds coalesce.

The mountains of Coronation Island lie athwart the wind’s southerly track. Thousand metre ramparts, they stand ice clad, embedded in the cloud-rack.

To surmount the range the air must rise, expand and cool at the saturated adiabatic lapse rate. The windward side of the island, by rain is permeated.

Passing over the peaks the air descends, contracting and warming at the steeply inclined dry adiabatic rate and ends at sea level warmer than previously.

This fohn wind crosses Normanna Strait engulfing ice-capped Signy Island in dry air causing its snow to ablate; leaving only that on the higher land.

|

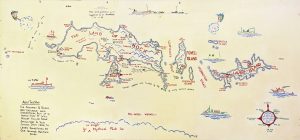

The Signy Wall Map

Bob Burton

During the demolition and removal of Tønsberg House in early 2002 a painted-over ‘fun map’ was discovered, recovered and sent back to the UK for restoration. The map, roughly 8 feet long, had been painted in midwinter 1957 by Robin Sherman. It occupied one wall of the eating area of the kitchen, which was converted into the carpentry shop in 1964. At some point it had been painted over.. Unfortunately, when the building was being taken down, the plywood panel was partly sawed-through before the map was seen.

The map includes a number of jocular references to circumstances in 1957 and to FIDS and visiting ships -the outline of HMS Protector is visible to the south of the islands. Although Robin Sherman was at Signy as a surveyor, his interest in this map was humour rather than accuracy. Hence Coronation Island was named “The Land of Hock” in recognition of Doug Bridger and his sterling efforts in completing the mapping of the island – “hock!” being his favourite though inexplicable expletive. Various additions were made later. They include references to the 26.4 mile dog sledge run made by Dave Statham and Derek Skilling in August 1957 and to the serious damage to RRS Shackleton by a bergy bit in November of the same year. The ‘fun map’, which was restored by Dave Burkitt, has been returned to summer-only Signy and is on display in the bunkroom corridor.

In 1964, Walter Dawson painted a replacement map in the dining room of the Plastic Palace. It broadly followed Robin’s original but left out those references – e.g. The Land of Hock!, that were a mystery to base members at the time.

Base Dentistry

L-R: Dental work (R.Sherman); Fergus O’Gorman examining Jim Stammers (J Stammers)

Building Foca Hut

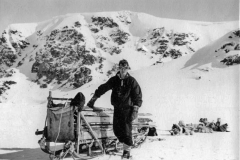

L-R: Transporting wood across to the west coast to build Foca Hut; Constructing Foca Hut. (J. Young)

Ice Flowers

Fergus O’Gorman

Winter was fast approaching. Temperatures were staying below zero for much of the day. The sea in Borge Bay was starting to film over into a thin layer of sea-ice. My first ice flowers were not daisies, chrysanthemums or buttercups. They were living in the sea-ice cracks. These were a mosaic of interesting ridges where the translucent film of liquid ice had started to break up into separate circular pans of ice. At the edge of the beach there was an accumulation of ice flowers. Every little wave thrown up on the beach instantly froze solid, providing the raw material for the developing crystal forest.

This ever changing pattern of ice-pans, tiny at first, was growing by the day with edges upturned. The patterns were wiped out by the first zephyr of wind sweeping in from North Point, touching one’s cheeks with frost nip, forcing movement or at least a harder tug on the anorak hood’s drawstring. If the wind gathered steam the Bay would quickly be a jumble of heaving plates of glistening ice sparkling in the low-lying sun whose shadows grew longer by the day.

It seemed a crime to walk through this field of flowers, leaving footprints crushed into the ice record to be instantly immortalised, consolidated and blended into a raised beach-line of ice of prehistoric proportions. One felt like early man in East Africa, leaving behind him at first a straight line, then a wandering of footsteps as hesitation set in as the distance from the temporarily sound ice formation close to shore increased, and the resonance of one’s weight rippled outwards across the still flexible sheet covering the fragile calm of the Bay.

If the wind rose into anything above a ripple, the fragile collection of sea-ice plates carefully, touchingly put together, would disintegrate in an instant to be flushed out into the Bay leaving the increasing sea- ice scattered, and the beach line piled with wafer-thin ice piled inches high at the edge, out of the sea’s reach. Soon these piles would grow to a height which required stepping over, and later into layers of frozen slabs of sea, now piled knee-high and requiring careful navigation.

When I saw ice flowers first, I dropped to my knees on the ice-covered beach. Their first blooming was where the calm sea ripples had come ashore and solidified. Sprouting in the frigid minus 10 degrees water-laden air from every crack were these delicate, fragile, transparent, hexagonal crystals of ice, growing upwards and branching sideways in front of my eyes as if by magic. Evolving and dissolving with every pulse of the tide. A first half-an-inch, then one, then two, and even three inches high or long, standing rigid until some unseen force caused them to fade away, and an instant later surge up alongside where the conditions were right.

As the onset of winter deepened, and when the weather allowed, I would, in the early morning, descend to the beach to see this festival of flowers, coming and going. Later in the winter, when I first went camping, I woke up surrounded by ice crystals, which was puzzling until I realised my breath was providing the necessary moisture. Of course when I turned the Primus on to turn a cup of iced water into a cup of tea, I was showered with a layer of crystals which had built up on the inside of the roof of the tent. These promptly melted, wetting the sleeping bags, and turned back to ice once the Primus was switched off. The following night the sleeping bags had to be hung in the apex of the tent to dry until we wanted to sleep and turned off the Primus heater, at which point the cycle began again.While this was annoying, what happened on the walls of the tent was more intriguing and much more fun. As soon as we occupied the inner pyramid of the seven-foot- high tent and the moisture level built up, layer upon layer of crystals grew out from the walls, starting at the floor and climbing up. But the advent of the Primus heat changed the dynamics of ice crystal build-up. By turning the knob and increasing the heat output, the layer of crystals would retreat down the walls, but as soon as the heat was turned down they reappeared, growing exponentially up the walls. As soon as I discovered how to do this, at the turn of my thumb, I got endless fun seeing the growing crystals continuing up or down the walls: there was little else to amuse one in a tent in the Antarctic, in the middle of winter! This soon got on the wick of my companion, and I was told I could only do it when he was outside taking care of the dogs, or for other purposes!

Even now, many Antarctic winters later, I can still vividly see those hexagonal crystals growing in front of my eyes. Like magic.

Click on the links below to get to a relevant page or use the pull down menu under the Stories tab.

| Timeline | 1950’s | 1980′s |

| Pre – 1947 | 1960’s | 1990’s |

| 1947-49 | 1970’s | 2000 on |