At the end of the 1990’s there were profound changes to the BAS research strategy and a new scientific programme structure was implemented. This saw the disappearance of the long established terrestrial, freshwater and marine programmes that originally underpinned research activities at Signy. Instead the station became focussed on long-term BAS penguin research studies, individual projects from within the new BAS programmes or UK universities and research projects conducted by international research partners.

The BAS complement now comprises a base commander, a facilities manager and a penguin project researcher who together operate the station each year and help support any non-BAS project scientists. There is no diving and, importantly, no boats so research is limited to the island. There is, inevitably, a very different atmosphere from that of the various wintering station incarnations and arguably not the same sense of family that wintering engendered, though any time spent on Signy is, of course, hugely memorable.

Left – Signy Station 2003 from the Cove; Station 2003 from the StoneChute (S. Coggins); Summer 2017-18 team Xmas card.

Demolition Doc

Mary Philipsz

As part of the environmental clean-up of BAS bases, a demolition team from Morrison’s was dispatched to Signy with me as medical officer. Arriving in typical Signy mank in mid-January 2002, no time was wasted with the unloading of cargo and establishment of Morrison’s camp behind Sørlle House. Seventeen people on base made for cosy meal times and time limits on hot showers!

L-R: The Station in November 2001; Signy Witch astride the Boatshed; Doc Mary on site; Twas ever thus – Signy Chef and Base Skua

Demolition work started with the Plastic Palace. Once the egg-box like exterior panels were removed the bolted steel skeleton came apart like a giant Meccano model, leaving the ground floor and concrete foundations as an ideal platform for the storage of outgoing demolition waste. (The foundations remain as a storage area that is visible from the drone pictures – Ed.)

The old fuel oil tank further up the hill took more careful planning. Most of the oil had been pumped out, leaving a residue of noxious sludge. In the event of a person working inside the tank being injured or overcome by fumes, rescue scenarios were practised. A large hole was cut in the side of the tank and, with the inspection hatches removed, this allowed adequate ventilation for the team to clear the remaining oil sludge. The inside of the tank was then cleaned before being cut into pallet-sized sections for removal. The last onerous task was the removal of tons of white sand from the bed of the foundation.

Demolition state of play by early February. The water reservoir still in place

Tønsberg House seemed to be held in more esteem than its 1960s fibre-glass successor. The well-constructed, fine timber frame was all numbered and with original government shipping stamps. Some timbers were salvaged and a wall map was uncovered. The BAS tradition of brushing up for Saturday night dinner was upheld with splendid food and entertainment which included horse racing, a pub quiz, air guitar demonstrations, a barbeque and an Easter egg competition. Sundays were ‘days off ’ and for the most part, the mank lifted and sunny Signy was revealed in all its compact glory. Most of the team took the opportunity to explore; skiing on the glacier, snorkelling in Factory Cove, checking out the penguin colonies at Gourlay or investigating the huts scattered around the island. (Who had lovingly stashed away treasured copies of Tractors Monthly in Cummings Hut?)

Was there much in the way of medical work? While there were several work-related injuries – fractured ribs, rusty nails through feet and minor abrasions and lacerations, there were more incidents involving recreational activities. For reasons of confidentiality,the owners of the fur seal-chomped thigh and penguin-bitten lip shall remain nameless. A few first aid classes were run and an improvised dark room was set up when a nasty ankle injury called for x-rays.

As demolition work was finished ahead of schedule, the team got stuck into many, much-needed projects to spruce up the base and its environs. Walkways were improved, the water reservoir demolished, the crosses at Cemetery Flats painted, the huts tidied and the new generator installed. Even the Signy Witch (the weather vane on the Genny Shed) was cleaned of rust and given a lick of paint.

L-R: View from Oil Tank to Orwell Glacier; By early March the Tank, Plastic Palace and Tonsberg are dismantled; Early April the reservoir has gone, the site cleared and Sorlle House is being closed up for the winter. Job done.

It took a full five days to embark the waste bundles and drums from the demolition onto Ernest Shackleton. As we left in early April, Factory Cove appeared neat and tidy, the buildings remaining all uniform in corrugated green but perhaps Signy was missing its echoes of the past: its history as a whaling station and the years when it had been a wintering FIDS and BAS base.

A Return to Signy

Fergus O’Gorman

I heaved out of my bunk at 0600. It was now November 2007 and 47 years since I had left Signy – apparently for good. The dawn had come and left the usual overcast sky. The m/v Ushuaia, an Argentinian cruise ship, appeared to be moving slowly. Had we anchored in Normanna? I dressed fast and jogged to the bridge. The Captain, Jorge Aldegheri, was conning the ship. We were heading away from Coronation towards Signy. “We’ll anchor at 0700 in Borge Bay” he said. “Roger Filer, a friend of both Nev Jones and me, is buried here”, I reminded him. He smiled sympathetically. From the flying bridge I scanned the island where we had wintered decades before. This was our first return to the island. It was going to be very emotional and full of nostalgia.

A zodiac went over the side. The first party was going ashore to meet Dave the new Base Commander. As I wanted to mount a private visit with Nev Jones to Gourlay Peninsula and visit Rogers’s grave, I needed to get Dave’s approval. Needless to say there were no difficulties. We shot back to the ship and I talked to the Captain about the visit to Gourlay. He kindly agreed to let us take a zodiac even though that would slow down the ferrying of the rest of the passengers ashore and might delay our departure for the next destination, Elephant Island.

|

Rushing breakfast, Nev and I jumped into a zodiac piloted by two of the Argentine crew and shot off. Once around Berntsen Point we headed directly to the Gourlay Peninsula and landed on Pantomime Point. How many times had I done this before? Countless. However, despite the distance in time it felt amazingly familiar. But something was missing. Where was the cacophony of sounds which had always greeted us? Where were the thousands of Adélies? We climbed up on the plateau. Here at last were the rookeries. Surprisingly discrete and very quiet. Of course it was early in the season. Had they all arrived? Or was the perception of many fewer penguins real? Was this another symptom of global warming and changing climate? With the increasing air and sea temperatures the Adélie’s range is retracting southwards along the Peninsula while the chinstraps have been expanding. |

We had come to visit Roger’s grave and pay our respects. He is buried close to where he fell to his death ringing sheathbills on the guano-covered ledges. Having paid our respects we each went our way; Nev to the hut he had built and I to sit close to the Adélies. Memories crowded in. The smell alone was sufficient to evoke a kaleidoscope of images.

Hurriedly I got up; the hour permitted having flashed by, and galloped back to the zodiac. Returning to the ship, we joined the last group heading for the Base and took the official tour. A quick view of the labs reminded me how times and techniques have changed. Now if its not electronic it’s not worthwhile. If you can’t download the data into the computer and use software to analyse it, forget it. Not like the seat of the pants stuff I remember: probing dove prions’ anae ( or is that anuses?) with old-fashioned thermometers for Lance Tickell. Or checking the heartbeat of nursing Weddells by creeping alongside and carefully placing a hand on their chests, or a thermometer up their bums! Happy thoughts – all part of the nostalgia and emotion of memories past.

But when I climbed up to Berntsen Point that all changed. I sat down on a rock, which I suspect still had the imprint of my rear end indented on it. Having carefully sat down, I lifted my head and looked towards Coronation. My jaw dropped. I stared in amazement at the scene, once so familiar, now utterly changed. I was shocked. The view which I had had of Coronation, reinforced almost daily by contemplating it from this very point, was so different. The island opposite, only 10 miles or so away, was no longer the pristine ice-encrusted landscape I remembered. Yes, Mount what-its-name –Nivea?- was still there, as was Spindle Cove and the Laws and Sunshine Glaciers. But the changes astonished me.

The Laws and Sunshine Glaciers had retreated almost out of sight. The panoramas of Mount Nivea and the valleys where only nunataks had protruded through the millennia-old caps of ice now lay bare. Every rock, it seemed, was now visible from head to toe, brown and black mountains and cliffs merely plastered with snow and ice which was clinging perilously to their slopes. Where in the past the snow and ice had dominated this coastline it now appeared like a remnant clinging despairingly to the sloping substrate, ready at any moment to slough off.

I turned my back on the view and contemplated the Signy uplands. Seen from here, the ice cap seemed significantly smaller. In fact, so much so – by up to a third – that a BAS geologist had mapped new rocky landscapes never before seen by man. I stood up, my nether regions familiarly chilled, and gazed one last time at Coronation and Signy, the views forever burned into my subconscious, forever changed.

Ice Retreat on Signy Island

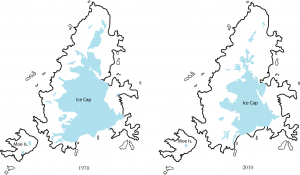

The BAS Mapping Group published topographic maps of Signy Island in 1970 and 2010. These have been used to generate two diagrams illustrating the significant shrinking of the Signy ice cap over four decades. The Orwell Glacier is now off limits whilst the Jane Col ice slope no longer exists. The ice cave in Paternoster Valley through which the outflow from Lake 3 (Changing Lake) flowed into Lake 1 (Sombre Lake) has disappeared with the retreat of the ice slope on Similarly, what was originally known as the Lake 9 ice slope that stretched from the northern end of the Snow Hills down Tranquil Valley to Lake 9 (Tranquil Lake) on the West Coast has also disappeared. Lake 16 (now Gneiss Lake) in the Gneiss Hills, which was permanently ice covered in the 1970’s, is now completely ice-free each summer.

The images below (2018 images, courtesy of Matt Jobson) illustrate some of these changes from a ground level perspective.

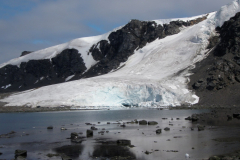

The view southwards up Moraine Valley in 1975 (left) and 2018 (right) – Significant Orwell Glacier retreat.

L-R: Manhaul Rock on Mcleod Glacier in 1975 – only the top 1 m was visible in 1965; Manhaul Rock viewed from Garnet in 2018; Manhaul Rock in 2018 with figure on top for scale

L-R: Orwell Glacier, no longer routinely traversed; Significant crevasse towards front of Orwell Glacier; Same crevasse from below.

The Modern Station and Field Huts

Pictures courtesy of Matt Jobson

Captions L to R: Late winter station; First relief with sea-ice; Station ice-free, note the fur seal fence across back slope; Open water relief using landing craft.

L to R: Station from above, captured on drone camera; Station buildings and jetty; Ellie seal invasion; Defences against ellies.

Captions L to R: Generators in Genny Shed; Main laboratory; Station Office; Living Room; Socialising in the Living Room; Kitchen area.

Captions L to R: New Foca Hut; Foca Hut entrance; Foca interior showing bunks; Foca interior showing worktop; L to R: Cummings Hut; Cummings interior; Waterpipe Hut; Waterpipe hut interior; L to R: Gourlay huts; Gourlay hut close-up.

……. and now some science

Since its transformation into a summer-only facility the station has operated for a further two decades, generating valuable research at a time when the polar regions are experiencing significant change and Signy Island is such an environmentally highly sensitive location. Below are examples of significant modern research at Signy which usefully build on our long term monitoring data and earlier research activities. Seven decades on and Signy is still delivering!

Mixed Fortunes and Intrepid Travels of the Signy Island Penguins and Petrels

Mike Dunn

(Signy Island Science Manager and Seabird Ecologist, 2001-present)

Signy Island is rich in birdlife, the different seabird species breeding there ranging from diminutive Wilson’s storm petrels and Antarctic prions nesting in rock crevices amongst the the many scree slopes and boulder fields, to the distinctive southern giant petrels which are to be found breeding and soaring along the cliff tops, rocky promontaries and coves of the west coast. Most well known are the three species of pygoscelid or brush-tailed penguin which annually breed on Signy: Adèlie, Chinstrap and Gentoo.

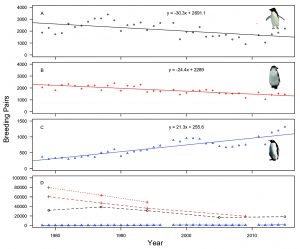

Since 1978 the British Antarctic Survey has operated an annual penguin monitoring program at Signy Island, carefully tracking numbers of breeding pairs and fledglings for all three penguin species. The results of these studies were recently published by BAS scientists working at Signy in the prestigious journal PLoS ONE(Dunn et al 2016). This revealed that although Adélie penguin breeding pairs increased in numbers from the late 1970s until the late 1980s, they have declined by as much as 42% since that time. A similar pattern was found in the case of chinstrap penguins which have steadily declined in numbers from the late 1970s until the present, a 68% population reduction. The story is not all bad however: gentoo penguins have bucked the declining trend seen in the other two species, instead undergoing a series of population fluctuations and an overall population increase of 255% since the 1980s. Nevertherless, total numbers of gentoo breeding pairs remain much lower than the more abundant Adèlie and chinstraps. Despite these very significant population changes, the numbers of chicks successfully fledged per nesting pair has remained stable for all three species. Although macaroni penguin pairs also nested in very small numbers in the past, this species has not nested at Signy for more than ten years.

A – Adelie breeding pairs, B – Chinstrap breeding pairs,

C – Gentoo breeding pairs, D – Total number of breeding pairs (M Dunn)

The changing population trends of the Signy Island penguins closely resemble similar patterns of change in these same species at a number of other sites located across the Scotia Arc and West Antarctic Peninsula, an area currently undergoing significant environmental change. The causes of these regional penguin population changes are as yet unclear, although increased over-winter mortality, particualrly amongst juveniles, is likely to be playing a significant part. Future studies by BAS scientists and their international colleagues hope to establish for certain the drivers of these population changes and the on-going work of the BAS seabird programme at Signy Island will remain an important component of this effort.

The results of a further long term seabird study at Signy Island – in this case of southern giant petrels over a 50 year period – were also recently published by BAS scientists in the journal Polar Biology (Dunn et al 2015). The first organised counts at Signy were in 1968, and 20 years ago a structured annual monitoring program was introduced to keep closer track on breeding numbers and success. The population trend for Signy’s southern giant petrels was similar to its penguins: a population decline of nearly 50%. However, there was also a steep reduction in breeding success (from 60% to 40%) in the last 10-20 years. Since the southern giant petrels breeding across the South Orkney Islands collectively make up an estimated 5-10% of the global population of this species, further declines across the islands would be of significant conservation concern. Consequently the Signy population will continue to be monitored closely, along with a number of other southern giant petrel populations across the Antarctic.

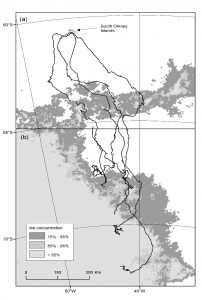

In addition to population monitoring, BAS scientists have made use of new technology to learn more about the at-sea distribution of Signy Island Adèlie penguins during winter. This is a time when the birds are no longer at Signy, adults and fledglings all having departed at the end of their annual breeding season. Adult Adèlie penguins from colonies at North Point and Gourlay Peninsula were fitted with either Global Location Sensors (geolocators) or Platform Transmitter Terminals (satellite transmitters). Geolocators are small (approximately 2cm) battery powered devices mounted on leg rings and measure the intensity of visible light every minute. Upon recovery of these devices the following spring during penguin recapture, analysis of this data allowed daily sunrise and sunset to be calculated and so converted to actual location estimates. The satellite transmitters are streamlined to reduce drag and fitted to the lower back of a penguin. When a bird is on the water surface the device sends regular positional fixes to a satelite, which can then be downloaded without the need to wait until device recovery. However, once the penguins begin their moult, these devices are lost as they are attached to the moulted outer feathers. Nevertheless, between the two methods Adèlie penguins were tracked over a nine month period from the time they departed their colonies at the end of their breeding season (January) until their return to Signy the following September. During that time, the Adèlies travelled south to the Weddell Sea pack where they moulted on the sea ice. Once they had completed their moult, the penguins spent the rest of the winter months travelling north or north-eastward within the expanding winter pack ice, before finally returning to Signy in late September and early October. Incredibly, during these journeys the penguins travelled distances of up to 2,235km – much further than previously thought. This study was published by BAS scientists in 2011 and is the first study to indicate the moult locations and winter dispersal patterns of Adèlie penguins in this region of the Antarctic, and also indicates the dependance of Adèlie penguins on sea ice habitat during winter.

Routes of five Adelie penguins tracked from Signy Island south to the pack ice overlain

on a typical ice concentration map for the January stage of their journey to final moult locations (M Dunn)

Current research is now taking place involving the tracking of Adèlie and chinstrap penguins from Signy and other South Orkney islands to determine which overwintering and summer foraging areas are consistently utilised in different years. During 2018, BAS scientists published research which showed that over multiple breeding seasons the krill-eating chinstrap penguins from Signy, Powell, Laurie and Monroe islands all foraged in areas frequently used during the same period of time by commercial krill fisheries. Such knowledge is essential in predicting the vulnerability of penguin species in this region.

When aliens invade…Antarctica!

Jesamine Bartlett

A long time ago, all the way back into the 1960s, a new experiment took place throughout the Antarctic region. Taking plants from one latitude and moving them to another seemed a harmless but effective way of testing their physiological resistance to the harsh wilds of the Antarctic. But, little did we know…

One such plant found itself uprooted from its home on South Georgia and relocated just a few steps up the Backslope from the base on Signy. It did not survive long with the grey mank days and relentless winds and soon perished. However, its stowaways survived. Hidden amongst the soil surrounding the roots were the small worm Christensenidrilus blocki and larvae of the flightless midge Eretmoptera murphyi. Both are native to South Georgia, neither is native to Signy. In fact, Signy Island has very little invertebrate life to write home about. Some small mites and collembola are all it has known since before the last ice age. No native ‘macro-invertebrates’ live there, and the introduction of E. murphyi has given it it’s first. In fact, this alien flightless midge is now the largest terrestrial organism on the island.

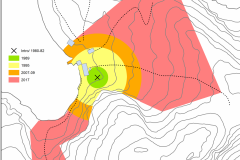

This midge settled in well, and over the decades has drastically expanded its range from the base to an area close to 85,000m2, stretching up and across the Backslope and to the top of the Stonechute. It can be found at densities of as many as 100,000 midges per sq. m. and shows no signs of slowing its spread. Signy Island is under a full-scale invasion.

Left – Eretmoptera murphyi adult ©Roger KeyCentre – The spread of Eretmoptera murphyi from the original point of introduction and discovery in the 1980’s to the latest survey results 2016/17.

Right – Jes sampling the Stonechute on a glorious dingle day.

Eretmoptera murphyi is unusual for a polar invertebrate in that it is asexual, with females able to produce clones of themselves. Without the need to find a mate, a midge does not need to time when it emerges in the summer. Essentially, she can develop into an adult whenever the timing and conditions suit, and therefore rather than have a single mass emergence event like its sexual cousin, Belgica antarctica on the Peninsula, E. murphyi can produce populations all through summer. In addition to this, these midges are tough, able to withstand the temperatures and annual freezing Signy endures, by rapidly cold hardening to dropping temperatures, tolerate drying out when the thin moss and soil layers lose water, but also respire when they flood. The midge is flightless, having lost its wings some time ago – a response to the cold that is often seen at the Polar latitudes. So, it can only get about as a wriggling larva, as a walking adult, or by catching a ride. Based on its current distribution range, and association with footpaths, it seems highly likely that it is us humans that spread this midge around on the treads of our boots, something we are trying to address in a revision of biosecurity protocols.

Whilst harmless enough, E. murphyi is a detritovore, eating dead organic matter built up in the moss and peat banks. This is making the soil more ‘humous’ than usual in places where E. murphyi is present. In an ecosystem with no significant invertebrates to break down the litter, moss banks become peat and remain so for millennia. But E. murphyi can turn peat into soil and add nutrients to it in the form of its own guano. They are doing the job of earthworms in an ecosystem that has never had such a creature.

The impacts of the midge invasion may take a few more decades to be realised, but already they amount to more than 2.5 times the mass of the native invertebrate population and are having an unmistakable affect on litter turnover. Our recent work has started to explore the soil chemistry to find out how much these tiny bugs are influencing the ecosystem. As many of you may well know, Antarctica is a nutrient poor environment, and small changes may have consequences to the native vegetation. Mosses tend not to love rich soils, and Signy has some of the finest examples of moss banks and vegetation in the Antarctic.

Whilst this all sounds very negative, take solace in the fact that because Signy is a basic ecosystem, we can learn a lot about the impacts of an invasive species from this accident. Understanding the linkages between species and un-weaving the webs created is the holy grail in ecosystem science. This is an unachievable feat in an ecosystem as complex as a rainforest, or even your own backgarden. But on Signy, as you will all well know, life is simpler! We may be able to unpick the island’s functions by monitoring the effect this alien is having.

And now for a twist in the tale! I have set the scene with E. murphyi as the villain of the piece. But let me introduce another: the beetle Trechisibus antarcticus. This predatory beetle has been disrupting invertebrate life on E.murphyi’s native South Georgia, decimating populations of herbivorous beetles, and possibly E.murphyi itself. In fact, E. murphyi has not been seen on South Georgia in years. Could it be that another invasive species has wiped it out? Well, truth be told we do not know for sure, but if true the only population in existence would be the alien population on Signy Island – Do we then need to consider protecting it? Should we, in fact, conserve the aliens?!

Click on the links below to get to a relevant page or use the pull down menu under the Stories tab.

| Timeline | 1950’s | 1980′s |

| Pre – 1947 | 1960’s | 1990’s |

| 1947-49 | 1970’s | 2000 on |