Research Changes

Through the late 40’s and 50’s the science had focussed largely on synoptic meteorological observations and survey work though some biology was also undertaken, notably by Dick Laws (elephant seals), Bill Sladen (birds) and Fergus O’Gorman (birds). The 1960’s marked a change in research strategy at Signy with the creation of marine, terrestrial and freshwater research projects (in 1963) which would eventually become the long term research programmes in the 1970’s that operated through to the mid-90’s. The decade saw the beginnings of the station’s scuba diving capability (1964), which became such a major feature of Signy life, as well as a further expansion of the station accommodation to handle the growing station complements. [Does anyone have stories of early diving? – Ed.]

Left: Barry Heywood chipping a sampling hole in lake ice (A D Bailey); Centre Left: Andy Bailey taking a soil core (P Tilbrook)

Centre Right: Diving from the dinghy (P Tilbrook); Right: Robin Sherman chainsawing a dive hole (A D Bailey).

[Below are three accounts of how the long term science programmes at Signy Island began – Ed]

Signy – The Moor House of the South

Martin Holdgate

(Head of Zoological Section 1961-67. Extracted from a speech at the 60th Anniversary Reunion 2007)

L-R: Martin Holdgate and Ron Pinder; Martin Holdgate admiring the view from Factory Bluffs.

By the late 1950s it was clear that a British presence in the Antarctic had to be justified by science. Upper atmosphere physics had its natural home at Halley Bay, while the geologists still had much to do along the Peninsula, but it was less obvious what to do about biology.

The FIDS Scientific Bureau, headed by Sir Raymond Priestley and Bunny Fuchs, thought Signy might be a good base for biology. At that time the Zoology Department at Durham had a nation-wide reputation for training first-class animal ecologists. Its dynamic (and eccentric) Professor, Jim Cragg, had made the National Nature Reserve of Moor House on top of the North Pennines his main study area, and there his students were systematically taking the ecosystem to bits, finding out how many of each species there were and how they interacted.

Bunny Fuchs invited Cragg to go south and look at Signy. He did so in the southern summer of 1957. But he had only had the briefest of looks when RRS Shackleton in which he was travelling hit a floe north of Laurie Island. However, he hoped that a FIDS Zoological Unit might be based at his department, where I was a lecturer. Unfortunately for both FIDS and the Department, Cragg’s appointment as FIDS zoological mentor was blocked by Raymond Priestley, so Bunny Fuchs instead joined forces with Professor Eric Smith at Queen Mary College, London.

In September 1961 I was a staff member of the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge and was somewhat at a loose end. At the FIDS Conference I found myself talking to Barry Heywood and Peter Tilbrook, who had been recruited to start the biological programme at Signy. It was soon clear that their preparatory training was minimal. I persuaded Bunny to send me down with them to help supervise their work and do the full evaluation of Signy’s potential that Jim Cragg had not been able to undertake.

I already knew that the island was home to many species of birds and seals, when we got there, I was impressed by the rich carpets of mosses and liverworts that spread over many lowland areas. So I decided to do a vegetation and soil survey – which would also help Pete Tilbrook structure his sampling of what the Base called ‘weirdies’.

Our arrival caused something of a culture shock. Russ Thompson, the Base Leader, had been told that ‘the boffins were coming’ and planned a laboratory, but thought we would be working on seals, so he specified doors that could accommodate a horizontal elephant! We didn’t need that – but Pete and Barry did need 24-hour power for insect extractors and aquaria. A reasonable little lab was contrived, but when I got home it was agreed that we had to have a proper, purpose-built new lab.

BAS (as FIDS had by now become) let me do the planning. Derek Gipps saw a photo in the newspapers of a two storey telephone exchange which Bakelite, the plastics company, had built in Birmingham. It was made of bolted-together resin and fibreglass sections, supported on a steel frame. Insulation was provided by phenolic foam sandwiched between the fibreglass. It looked as if the style of construction would work in the Antarctic. Bunny and I went to have a look at it (travelling in his E-type Jag) and that was how the Signy ‘Plastic Palace’ came to be commissioned.

Our biological work at Signy was really a Moor House research programme transported to the south. Step by step the soil, plant communities and different groups of little animals living in the soil and vegetation were described and their interactions documented. It was by far the most comprehensive ecological study ever done in the Antarctic up to that time. Similarly, Barry Heywood’s research on the Signy lakes was also in its time the most thorough exploration of a freshwater Antarctic ecosystem. The birds and seals were also far from neglected, and the work on land was flanked by an expanding programme in the inshore seas, especially as SCUBA diving became an accepted method of working. The creation of long-term reference sites allows long term trends – starting with those caused by the fur seal population explosion and moving on to the impacts of climate change – to be documented.

I am somewhat sad that Signy is no longer a full-time biological research station and that the Plastic Palace has gone. I feel it was historic in its way – but I believe that BAS and all those who took part in the work can take pride in some very good science that in its time was a world leader.

First Steps in the Biological Programme

Peter Tilbrook

Back in 1962 as a raw graduate, I was recruited to FIDS as one of two biologists (as opposed to Met men and others doing biological studies) to set up a biological research programme at Signy.

My Prof at Durham, Jim Cragg, had been asked by FIDS to visit Signy the previous year to suss out the suitability of starting such a programme there. Unfortunately he was on the Shackleton when it got holed by ice near the South Orkneys so his visit was curtailed. But he was enthusiastic about the research potential and suggested that plans went ahead. So when Bill Sloman visited Durham University on one of his recruiting rounds, Prof Cragg, knowing of my interest in polar environments (from a visit to Spitzbergen), whipped me out of my finals practical for an interview with Bill.

I was duly signed up to go South in 1962. Unfortunately, Cragg’s involvement stopped there. He had apparently trodden on a few diplomatic toes while in the Falklands, so his services were not retained! Instead, the job of ‘supervising’ the first British programme of biological research was given to Prof J F Smith of QMC London and I’ll never forget my first meeting with him. As the first FIDS biologists to go south to Signy, Barry Heywood and I went to QMC to be inducted, or so we expected, on the programme of work. This delightful, but busy Prof (a marine biologist) greeted us in his office and his first words were “Well, what are you planning to do while you’re down there?”

So started the FIDS/BAS biological research programme. As our brief was to research the ‘natural environment’ of Signy Island,we naturally decided to spread our attention across terrestrial (my focus), freshwater (Barry’s) and marine (jointly) systems – a modest little undertaking! So, in the 2-3 months before leaving, we set about ordering collecting gear to serve all three environments.

Fortunately for us, and for Antarctic Science(!), Martin Holdgate (who had also been one of my lecturers at Durham) decided to come South with us for part of the first (62-63) summer. Even this resulted purely by chance though, as I bumped into him while in the coffee queue during our induction course at the Scott Polar Institute. Already an experienced field biologist with expeditions to Southern Ocean islands, when he heard where I was off to and the situation, there was only a moment’s thought before he was off to the front of the queue to speak to Bunny Fuchs. Within minutes all was arranged. Oh, the freedom and flexibilityof those days – though hardly the recommended way to embark on a major new programme of work. Anyway, Martin’s advice was invaluable to our final UK preparations and getting programmes started on base and, of course, led to his long term involvement with polar biology.

So began the biological programme at Signy. After some desultory attempts to collect specimens from the sea we quickly bowed to the obvious – that the marine system required a separate programme – and Barry and I concentrated on freshwater and terrestrial respectively. Initially, some pretty basic needs had to be addressed. Tønsberg House had to be modified to provide laboratory space. Twenty four hour power was also required to run equipment (previously the base generators had only operated for part of each day), so a new genny shed had to be constructed. This was all achieved in true Fids fashion – much swearing and ribaldry but tremendous cooperation, innovation and effort, particularly from our diesel mech.

Barry and I had to develop techniques ‘on the hoof ’. Collecting cores from frozen moss and sampling from ice-covered lakes were major problems. To sample regularly in winter, for example, I needed to design and build a corer to run off an electric drill and then deploy one of the generators (not in those days one of the portable variety) at my main experimental site on the slope about 200m behind the base hut.

L-R: Peter and his “portable’ field generator; taking cores from the Backslope study site; Peter and the green Mutt.

One amusing incident, which got transmogrified several decades later, revolved around a project on sheathbills. This included monitoring the birds around the base. One day we fished a ‘mutt’ out of the sea in poor shape and put it in the workshop to dry out. On returning later we found it had become active enough to get into an open pot of green paint. A long process of cleaning then began but the mutt never lost its green colour (see photo) and was persecuted by its peer group when released. This story somehow got mangled by Bunny Fuchs’ in Of Ice and Men (p236). He told how a husky called Mutt fell into a large bucket of green paint – not realising that ‘mutt’ is a nickname for a sheathbill – and gave a completely fictitious description of the effect on the dog.

Somehow we made progress through that first year and by the ’63 -’64 summer marine biologists had been recruited and diving started. From then on biological research developed apace. I played a role in this expanding programme until leaving in 1975 – but from humble beginnings ……. !

A Question of Scale

Barry Heywood

I remember vividly sharing the astonishment that Peter Tilbrook felt when Professor Eric Smith, whom we thought was to guide the development of Signy Island as a biological base, asked us what we were intending to do during our stay there. I also remember the discussions with Peter on how best to spend the magnificent sum of £250 on equipment to investigate the terrestrial, freshwater and marine systems of the island! Most of the money went on a microscope which we both realised was essential for whatever we decided to do. We also managed to borrow some equipment; soil extraction apparatus, a Nansen bottle with reversing thermometers, and plankton sampling nets. Thank goodness we were able to ‘borrow’ Martin Holdgate for that first summer too! After exploratory sampling of all the lakes and pools on Signy Island, I was able to discuss my proposed research with him and to agree on an equipment and chemicals list which he was successful in obtaining for me for my second year. It was like Christmas when RRS Shackleton came in the next summer. I received an oxygen probe, light probes, chemicals and laboratory glassware and even a small keel-less lightweight boat!

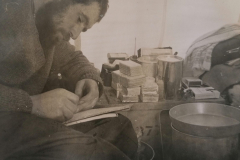

Summers were the most arduous times, whether standing in thigh waders in 1m of near-freezing water in order to cast my sampling nets into the trough areas of the lake (1st year) or sitting for hours in the lightweight boat with its minimal freeboard (2nd year). Obtaining snow from the back slope in summer to distil for the chemistry was an often time-consuming summer chore. Winter work was relatively comfortable by contrast. Hacking a hole through the 1 m thick ice with an ice chisel was warm work for several hours and the actual sampling of the lake could only be carried out in the relative comfort of a primus-warmed tent to prevent the wet equipment from freezing. Sampling could take six to eight days in winter and the nights were spent camped by the side of the lake.

I remain extremely grateful to the several Fids who volunteered time and time again to help me with my fieldwork during that first summer and winter, and to Andy Bailey, who acted as my GA throughout the following two summers and winter, although he had a research programme of his own. During this latter period there was a lot of equipment to be backpacked round the island, and samples to return to the Base. Using the dogs to sledge round to the west coast lakes provided memorable moments during the1963 winter.

I was most proud of a closing net I designed to investigate seasonal variation in the vertical distribution of the animals. Closure was by two aluminium half doors powered by bundles of four ordinary office rubber bands. Unfortunately, they perished rapidly even in summer and had to be replaced between individual hauls. My fingers still ache at the memory of renewing rubber bands whilst wet and cold.

L-R: The Heywood modified zooplankton sampling net; deploying an NIO bottle to profile water chemistry and temperature

I was fortunate in being able stay with BAS until I retired 37½ years later, and so was able to supervise the development of what would become a very productive Freshwater Unit. I had the good fortune in later years to SCUBA dive in the lakes on Signy and to work on the epishelf lakes on Alexander Island. The latter are permanently covered with 2.5m – 4.5m thick ice and are freshwater layers overlying marine waters. Fortunately, by then, a chance glance through a Canadian ice fishing magazine had introduced me to the Jiffy Drill which could cut through freshwater ice like a knife through butter. It was a boon to me and later generations of limnologists.

It was after my Alexander Island work that Dick Laws asked me to take charge of the BAS Offshore Biological Programme.“It’s only a question of scale” I thought so…………but that’s another story!

The Gourlay Hut (Hunting Lodge)

Nev Jones

The Gourlay Hut was built in 1961 and was still in use when Fergus O’Gorman and I visited in November 2006. This must be a pretty good record for a cobbled-up building! This is the story of its creation.

On 13 February 1961 Roger Filer died in a tragic accident whilst undertaking his studies of sheathbills on the Gourlay Peninsula. I was moss hunting in South Georgia with Stanley Greene at the time of the accident and on my return to Signy I requested permission to continue Roger’s work. He had ringed a large number of ‘mutts’ as well as having marked a considerable number of nests at Gourlay. It would have been a great shame if this groundwork had been lost. I was released from my full duties as a Met Assistant during the next (my last) summer season. Visiting Gourlay almost daily was not very attractive so we agreed that it would be a good idea to build a hut that would allow intensive recording of the birds as well as supplementing the ‘holiday’ facility that already existed at Foca.

As it was not possible to have a prefabricated building, the hut had to be created from the materials available. The old whaling plan near the base hut provided a few baulks of timber for the foundations. Glacier stakes were ‘borrowed’ from Russ Thompson for the framework. Spare tongue-and-groove planks were available on base for the roof and floor. Three-ply and hardboard sheets were used for the walls. Derek Clarke made a window frame. The door of the coal house was also borrowed. There was only one spare bed base available. Only enough roofing felt was available at the time to cover the roof. A pyramid tent was used during the building period and subsequently as a store.

These materials were sledged over to Gourlay during September/October. My diary shows that Derek, Russ, me and Susie’s team sledged the last load of materials on 20 October. Derek and I backpacked over and set up camp in the tent on the 24th. It was a period of mixed weather (of course) and it took us six days to complete the basic structure which was described as ‘draught proof but not water proof’ on the 30th. Derek returned to base and I moved into the hut on the 31st ‘because it was drier than the tent’! It had one bed and sleeping bag, a Primus stove, a paraffin heater and a radio in a ration box. I had also been lent a transistor radio by Ron Pinder – it was very useful company for about a week before it fell silent!

The first visitors arrived on the 2nd October when Derek, Ron and Russ turned up with Susie’s team. Penguin eggs were collected and I returned to Base with the party on sea ice that was breaking up. I returned overland with Dyke as company. After creating a small span near the hut it became a visiting site for two dogs after each visit to Base. I usually returned for a night, about once every 7-10 days, for a bath and fresh bread. Day visitors were fairly frequent and some stayed overnight – on the floor! The hut was finally covered in felting and sealed with Ruberoid by mid-March when I returned to Base. My last visit to Gourlay was on 5 April before I departed Signy Island on the 6th.

L-R: Nev Jones at the Hunting Lodge 2006; Ron Pinder contacting Base, using a Morse key.

I certainly never expected to return South so it was a moving experience to visit the Peninsula on 20 November 2006. Hunting Lodge was still standing and occupied but its days were numbered because two new huts were being built. I wonder how many Fids used it and stayed in it? (Lots. Ed)

The Prefabricated Plastic Palace

Barry Goodman

The “Shack” arrived at Signy on the 8 December, 1963 and while us serfs started unloading, the specialist building team were planning the site, counting all the bits, and finding that crucial bolts to fasten the hut to the foundations had not been supplied. Apparently they fell into the gap between two subcontracts. Whilst hasty arrangements were made to get them fabricated in Stanley, the 27 concrete base blocks for the stanchions were being prepared, with scenes that were reminiscent of Dartmoor Prison work parties.

Left: Building the concrete base blocks; Right: Flooring the ground level steelwork

Meanwhile, the new arrivals were sleeping in the roof of Tønsberg House, and pretty noisome it was too, made worse by the addition of a chinstrap penguin on Christmas Eve. Underneath, Walt Dawson and Charlie Spaans were taking out the partitions to make room for the generators. They found that the partitions supported the roof beams and hence the sleeping quarters. Hasty temporary shoring was arranged to allow for co-existence.

A concrete foundation ‘stone’ with cunning lettering was laid by Sir Vivian Fuchs on 16 January. The date on the stone shows the 15th but the “Shack” came in a day later than expected, and concrete isn’t as forgiving as wood. Hanging the ground floor fibreglass panels came next, followed by the flooring.

By 24 January all the lower cladding sections had been hung, but with some difficulty as they appeared to have warped somewhat in transit, and needed a bit of ‘persuasion’ to fit. After some tribulations the outer shell was completed even though we had to resort to using a Spanish windlass (a bit like a giant garrotte) to try to get the top shell the same size as the bottom. At one point the piece of scaffold pole being used to tighten the cable round the hut became unsecured, unwinding like a propeller, and nutting Joe Sutherland in the process!The scheme failed because the mastic used between the hut units was not designed for low temperatures, so did not ‘squish’ properly. As there was not much we could do about it, the top and bottom halves were bolted together slightly askew. Fitting out internally then continued apace, with the concrete floor in the wet lab being laid and internal partitioning spreading everywhere. The chief concern was to prepare the bunk rooms so that the sleepers could transfer from Tønsberg House and allow the diesel-electric team to complete their works. Occupation (sleeping only) commenced on 2 March and chilly it was too. The kitchen stove was fitted and was alight on 12 March which helped a little.

The Generator Story

With the dawning of the Age of Enlightenment on Signy and the expansion of the scientific facilities came a need for more electrical power to keep this new community in the comfort they deserved. To this end, the new base hut was to be heated and powered by two Rolls Dale 60kva units. They weighed about 2 tons each and had to be offloaded onto the jetty then hauled up to and into Tønsberg House. So the jetty had to be rebuilt and a lifting stick was erected at the end. In view of its size this was quite an epic in itself, as a small derrick was needed to lift it into place. The main lifting wire on a 3 and 2 purchase ran to a winch secured to the Plan. A secondary winch was also set up to haul the bogies up the railway line on the jetty and plan.

L-R: Unloading cases onto railway carts on the jetty; Winching one of two pennies into its new home; The Signy Light Railway.

Unloading started with one of the lighter cases, only 1 ton, to practise on. This was a good idea as the hauling teams were operating on a tug-o’-war basis and were nearly pulled through their own pulley blocks. It took a bit of working out as to who should be hauling and who slacking off. When it came to the generators, everything worked fairly well. A ramp was made into the new generator shed constructed of 6×6 timbers, copious quantities of 6” tacks and a bit of drystone walling underneath for good measure. The hauling wire ran from the winch on the plan and around a series of strategically placed stakes hammered into the back slope. This scheme was tried all day, with successively larger and more secure stakes. However they continued to get pulled out faster than a Fid’s teeth in Stanley.

Eventually, it was decided to try fixing the upper anchorage point to the new engine beds, on the grounds that if the beds pulled out we wouldn’t want the generators anyway. This succeeded in moving the load two or three feet up the ramp, but then the winch and its concrete base started to come loose. It was now attached directly to the engine beds and this finally did the job. In two days the generators were inside and the outside doors were shut amid general sighs of relief.

12 May The Plastic Palace had warmth and running water. This was more like it. Leave the rugged bit for outdoors and keep it there!

Ginge, the Signy Cat

Bob Burton

My earliest memory of Ginge is watching him trying to look inconspicuous in the snow. He was failing miserably. Ginge was already a Base feature when I arrived at Signy in November, 1963 and we were building the Plastic Palace to transform the old Fid base into a forcing house of science. Ginge had been tempted outdoors by the unusual sunshine, and he was stalking a group of sheathbills with all the sinuous stealth of his kind. Of course, he had no hope of getting within striking distance. As he slunk towards the sheathbills, they simply scuttled away. Then, circling behind him, they showed their contempt for the hunter by pecking his tail as it twitched in anticipation. Watching from the windows, we were amused by Ginge’s frustration and ignominy. This was his function as Base Cat. Along with the ancient gramophone records and year-old magazines he was one of the few sources of entertainment.

I appreciated Ginge for his company when I was on night met. duty. Time hung heavily after the base had gone to bed, and Signy weather is not wildly exciting. Ginge would stretch out on my knee, purring comfortably, while I drank cups of coffee or dozed the hours away. How long Ginge had lived at Signy we did not know; he was part of the fixtures and fittings. It was said that he was slightly odd, neurotic even, because of his long exile from the company of other cats; but who can fathom the psyche of a cat? This was surely only another instance of endowing a pet with our own attributes. We would certainly become odd or neurotic if we had to live at Signy for as long as Ginge. We would eventually go home but Ginge, it seemed, was there for all his lives.It was Ginge’s habit to wander into the kitchen and mew repeatedly. ‘Hello, Ginge! Dinnertime already, is it?’ And the cook would open a tin of stewing steak and spoon it into Ginge’s bowl. Sometimes the offering was dismissed with a sniff and the mewing continued. So a tin of sardines was opened, and then ‘herrings-in’. Yet still Ginge mewed, looking up wistfully at the cook. ‘You’re thirsty, then?’ and the operation was repeated with water followed by evaporated milk, with similar negative results. Only those who knew their cats recognised that all Ginge asked was affection. He just wanted to be stroked and spoken to, although a cuddle and a scratch behind the ears would be nicer.

Ginge was one of those talkative cats, perhaps because of a dash of Oriental in his blood. This was a trait that once gave me the fright of my life. One night I was seated in the met. office, long past midnight. It was as quiet as the grave except for the wind sighing in the aerials. I have always been edgy at night and the piercing shriek behind me stood my hair on end. I sat paralysed for a very long few seconds before I could steel myself to look over my shoulder. There, of course, was Ginge, tail up, coming to keep me company. So Ginge kept us entertained and earned his tins of meat and fish and his comfortable blanket-lined box by the kitchen stove. Unfortunately, like so many cats, he had the unforgivable habit of killing birds. He may not have had much luck with the sheathbills during the day, but his nocturnal forays after petrels shuffling to their burrows on the Back Slope were devastating. The skuas had no idea.One day, higher authority (in the person of Martin Holdgate) decided we could no longer keep a carnivore that was killing the very wildlife we were supposed to be studying. So Ginge had to go. There was dark talk of him being taken out and shot. At this point fate stepped in and I developed a raging toothache that neither aspirins nor the rum ration could quell. It’s an ill wind, they say, and Ginge won a reprieve. I was packed off to the dentist at Port Stanley and Ginge was allowed to come with me.

The voyage on the Kista Dan was rough and miserable for man and cat. On the first day, we ran into a storm and I was confined to my bunk in the fo’csle, feeling utterly wretched. As the bows plunged over the crest of each roller and my bunk dropped beneath me, I went into free fall, then flattened into the mattress as the bows reared again to meet the next heaving wall of water. At each buck and plunge our baggage went sliding up and down outside the cabin. Among the cases was Ginge’s travelling box. From inside came a pitiful wail that changed pitch as the box shuffled past the door. It was a unique demonstration of the Doppler effect. There must have been moments when Ginge felt that a quick death from a bullet would have been the better option. Me too; I could do nothing to comfort him until next morning when, dodging the spray, we hurried aft to the main accommodation. There I found a cat-loving ship’s cook who occupied a more stable part of the ship and was happy to care for Ginge, while I returned to the fo’csle to nurse my aching tooth and queasy stomach.

Four days later, we reached Stanley and Ginge was handed over to his new family. I was duly drilled, filled and sent back to Signy, but to a different routine. Now I played endless games of patience during the night watches. Ginge was no longer a part of our lives, and the last I heard was that he had been taken back to the UK, to a happy retirement where nights are warm and the milk fresh. And if his tail twitched while he slept, it was only because he was dreaming of catching those **** sheathbills.

A Base Leader’s Dilemma

Peter Tilbrook

The chance scanning through a medical book led to a complicated situation in 1962. I had been appointed as Base Leader before arriving at the base in December 1961 and soon realised that with no one with any medical training or expertise amongst us, and being a biologist to boot (i.e. I had dissected all sorts of relevant animals like frogs and dogfish!) I should probably assume the role of i.c. medical matters.

I would occasionally browse through the one standard medical book in the base office and I happened to read about ‘hernia’ – where a small section of the lower intestine periodically protrudes through the abdominal wall.

This came as quite a shock because for some time I had experienced a strange situation of having a lump in the groin area which could be pushed back into its ‘home’. Naively, I had no idea what this was and had not mentioned it to anyone as there was no pain or significant discomfort. There, under ‘hernia’, was a description of just such a phenomenon, so I read it carefully and tried to decide what to do about it. There was reference to the use of a truss to try to prevent the occasional protrusion.

The home-made truss.

I decided to try to live with this problem until returning to the UK and set about making a truss from materials available. The photo shows what resulted and this served me well in preventing the intestine from protruding through the hole, and I hoped this would prevent some of the more severe side effects such as ‘strangulation’.

Having decided not to share this news with anyone (in hindsight not a wise course of action) I continued normal base and fieldwork activities without any adverse effects. Unfortunately, the matter did impinge on my responsibilities on 31 August 1963.

On a rare calm sunny day with perfect sea ice conditions, Fred Topliffe and Pete Hobbs were to walk across to Coronation Island and climb Wave Peak. With Fred an experienced hill walker/climber and the day so ideal, this seemed quite OK.

Just before lunchtime someone with binoculars alerted us that one figure was heading down the glacier. So, assuming the worst, we prepared for a crevasse accident and loaded a sledge. At 2pm, Andy Bailey, John Chambers, Barry Heywood and I set off, pulling the loaded sledge across the sea ice. Meeting Pete about half way across to Coronation Island we learnt that Fred had indeed disappeared through a hole and into a crevasse and that Pete could not see or make contact with him.

What had been particularly worrying me was the prospect of getting physically involved with a rope work rescue and the effect it might have on the hernia and my efficiency. In view of this, I told the others of the hernia.

We left the sledge at Shingle Cove hut and started up the glacier. After only 20 minutes we saw a single figure coming over the ridge and it could only have been Fred.

The Wave Peak Saga – continued

Fred Topliffe

In late August 1963, as sound, level sea ice had formed between Signy and Coronation Island, Pete Hobbs and I discussed the possibility of climbing Wave Peak. It had never been attempted during our stay or I believe for some years previously. On 31 August conditions seemed ideal so we set off.

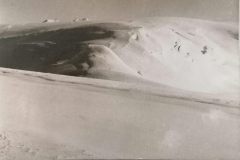

Left – The familiar winter view of Coronation Island;

Centre – 30 October 1963 – Shingle Cove (start of the successful ascent of Wave Peak.

Andy & Barry are in picture. Barry decided not to make the ascent). Right – The Anemometer marks the spot.

The crossing to Shingle Cove was uneventful and we started up the eastern slope to the right of the mountain. When we reached approximately the level of the top of the anemometer tower in Fig. 2, I fell through the lid of a completely bridged and invisible crevasse.

Pete could not see me and, getting no response to his shouts, he made the sensible decision to return to base following our footsteps. After a short while I regained consciousness to find myself about 40 feet down with my rucksack and ice axe about 5 feet above me. I was able to climb up and retrieve them and then many years of caving experience came to my aid. I treated the crevasse as a chimney, bracing my back on one wall while cutting steps in the opposite one. It took about 4 hours to regain the surface as I was cutting larger steps than was strictly necessary, not wanting to risk another fall. I found Pete had marked the crevasse with an ice axe and his returning tracks were obvious. Retracing our route I met the ascending rescue party who had left their sledge in Shingle Cove. I did not know about Peter’s hernia so I had no idea of the dilemma I had placed him in.

Lessons were learned from this experience, but it actually made me more determined to climb the mountain and on 30 October, as ice conditions were still good, Peter Tilbrook, Andy Bailey, Barry Heywood and I set off across the sea-ice to Shingle Cove.

The ascent this time proved uneventful and relatively easy. On reaching the top the views were captured for posterity.

On left – Andy and me (or possibly Peter) on the summit. On right – The Base Leader surveying his domain for the first time.

Recent visitors to Signy may have difficulty recognising the snow-covered landscapes in these photographs.

The Naval Engagement with the Drifting Thunderbox

Paul Pilkington

The year is 1964 and the location is somewhere in the Weddell Sea 900 km south-west of South Georgia. During the spring of the previous year a new base hut was built adjacent to the existing site and consisted of a 2-storey fibreglass pre-fabricated construction complete with provision for a toilet within the building. This inclusion did not sit well with the base members who demanded that a new outhouse be constructed next to the new building. Joe the carpenter got busy constructing a brand new outhouse made from discarded packing timber.

The question was then raised as to what should become of our old faithful thunderbox which had served us well for a number of years. It was located at the far end of the old building with a 10 m rope and post guide rail to enable safe access in the event of blizzards and zero visibility. In order to prevent any visitors from having to go to the trouble of donning bad-weather gear only to find it occupied on arrival a flag would be placed in a holder outside the outhouse door during the day by the incumbent and a red battery-powered lamp would be illuminated at night. At some stage the outside had been painted black and some wag had painted TEAS in large white letters on one of the walls.

When the determination of the fate of our now redundant asset came to be decided, it was voted unanimously that it should be pushed on to the sea-ice and with good fortune we could watch it float away when the ice broke out (and we could take photographs of the event), which eventually occurred.

A short time later the ice had cleared sufficiently for HMS Protector to enter our vicinity. In my capacity of radio operator I received a W/T (wireless telegraph) signal from Protector that they wished to communicate by R/T (radio telephone). The connection was then established. The conversation went something like this:

Protector to Signy – Gunnery officer here

Signy – Protector, go ahead

Protector – Signy, do you know anything about a shed floating on a block of sea-ice with TEAS marked on it?

Signy – Affirmative, Protector

Protector – Can we use it for target practice? (The implication was that they intended to range their four-inch gun on it.)

Signy – We have no objection

End of chat

When Protector paid us a visit a few weeks later I asked the gunnery officer how successful they were with their target practice. His reply was that they had scored a direct hit. What a shame that we were not there to photograph it!

The Danish Appendectomy

Bob Burton

Based on the Base Diary and some dim memories!

The Kista Dan came in on 11 January 1966 very late in the evening. Apart from 4 tons of regular cargo, they had on board Ray Adie, Derek Gipps, Mrs Coleman – wife of the magistrate at KEP en route for South Georgia, and a Daily Express reporter on a jolly. There were also our new doctor, John Brotherhood, soon to be nicknamed ‘Botherhood’, and Ron Lloyd on his way to be Halley Bay doc. They had a unusual request: they wanted to use the chemistry lab to remove the appendix of one of Kista’s stewards, probably called Hans!

Hans had complained of stomach pains in Stanley but, when the doctor learned how much he was drinking, he was sent away with a flea in his ear. However, after leaving Stanley, acute appendicitis was diagnosed. The nearest hospital was at South Georgia, Kista’s next stop after Signy, but the decision was taken to operate at Signy, in case the problem became worse while on the high seas to SG. Moreover, John Brotherhood was getting off at Signy, so only one doctor would have been left on board.

Chas Howie, Ron Lewis-Smith and Barry Goodman cleared the lab, scrubbed it out and, dressed in long rubber gloves, white lab coats and waders, wiped everything down with Lysol to assassinate all germs. Ron Lloyd was going to do the cutting; John Bro/Botherhood was to be anaesthetist with soil microbiologist John Baker as assistant. Colin Herbert did the dirty jobs and Mike Northover was spare man and photographer whilst Chas was outside backup man.

While sterilising was being completed, the highly-skilled medicos could be seen reading their textbooks with frowns of concentration. Meanwhile John Baker was sterilising all the sheets, pyjamas, bandages (for the surgical team – see photos) before Hans was helped into the lab. He was clearly in a great deal of pain.The big danger was ether accumulating on the floor and exploding it got near a naked flame or electrical spark Not that there was much that we could do to prevent it except turn off all non-essential electrical appliances. At the first waft of ether, however, Mike Northover keeled over and had to be dragged out; Chas took over.

The operation was finished about 11pm and the patient carted upstairs to bed. Frank, first mate on the Kista, stayed to talk to him in Danish when he came round and left a tape recording full of reassurance, information on Kista’s plans and a handy Danish/English glossary of medical terms.

Hans recovered well and left when Kista returned from relieving Halley Bay. He went on board with his appendix in a bottle and a Brenda Lee LP which he had played non-stop every day and which we never wanted to hear again!

Hydrographic Surveys

Cynan Ellis-Evans (based on imagery and notes from John Edwards)

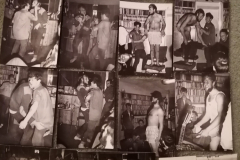

The Royal Navy has undertaken an enormous amount of hydrographic surveys in the BAT and around South Georgia over the decades and various RN ice patrol ships have visited Signy in the course of this work. HMS Protector came to Signy in February 1968 and put in an 8 man party in the hydrographic launch “Nimrod” for a two week work programme surveying the coastal waters of the island. The left-hand image below shows five of the party (L to R in the boat: Peter Odling Smee, Bill, Goldie, Knocker and Robbie – no further detail available) in their launch enjoying the Signy mank. The collage of photo prints show the HMS Protector, a couple of Royal Navy Whirlwind helicopters on Bernsten (I think) and a series of images of the group enjoying the hospitality of the Base and performing their somewhat salacious “interpretation” of “Old McDonalds Farm”. It all brings back rather unsettling memories of boozy rugby club after-match parties!

The Bodger Whale Day

John ‘Percy’ Edwards

The 13th of January 1969 was an eventful day that came to be known as ‘The Bodger Whale Day’. My diary records:

‘Black Monday for Harry ‘Buck’ Taylor & Jake Howarth [wireless operators] as they went to Gourlay (by boat) and got stuck in Paal Harbour. They had to be rescued by the ‘rugged’ Met.men & B.C. A mega loss was the ‘Voice of Signy’, Spanner’s (chef Alan Spencer) radio which with several bottles of beer and clothing ended up in the og. A rescue attempt was made but was unsuccessful, despite ‘Floppy’ [Paul Finigan] donning an immersion suit.

Roger Liddall [Diesel Mech] walked over to Gourlay the normal way and reported a big whale had been washed up. This explained Les Graves’ report to Jim ‘The Laird’ Conroy that there were unusually ‘thousands of G.P.s at Gourlay’. The next day I was ‘up at 6.30am and off to Gourlay with Roger, Doug Bone & George Holtom to see Roger’s whale. It was high & dry and was stripped of most of its skin by G.P.s. We measured it as 28.5 ft long with 6 ft wide tail flukes and it appeared to be a young fin whale as the RHS baleen plates were black at the rear of the mouth, changing to white anteriorly, while those on the LHS were black on their outer side and white inside. I cut out a few plates and later collected a whale harpoon head from Factory Cove.

More people visited the whale the following day and the base diary, written by Eric Twelves, records ‘Famous Fin Whale being devoured by hordes of greedy G.P.s. So far Jim hasn’t even caught any despite his optimistic estimate that ‘he expected to catch a couple of hundred’.

The skua dispute outside the kitchen continues with no apparent change of territorial border. C.I.A., however, have indicated that the Northern Pair are being aided by Russian advisors and a massive air strike is imminent.’

Buck Taylor still was not having much luck with his wanderings as he ‘went to Foca but was attacked by skuas and fell into the smallest lake in Three Lakes Valley and so came back to base. Will be fitted with a cow bell!’

By the 2 February the remains of ‘Bodger’s Whale ‘ had disappeared, washed away on a higher than usual tide.

Man-hauling to the Sandefjords

John Edwards. Photos by Martin Pinder

The 1960s had not been a great decade for travel on Coronation. There was a trip across the sea-ice to SandefjordBay with two dog teams in October 1960 but a later attempt to sledge overland onto Pomona Plateau was foiled by crevassing. Wave Peak was climbed in October 1963 by Bailey, Tilbrook and Topliffe (see above) and Cape Meier was reached in Desmarestia in 1966. In November 1966 Lindsay, Burgin and Thornley climbed the west face of Devil’s Peak and two days later the last two ascended Wave Peak with Smith. Apart from these ventures, however, hardly anyone had set foot on Coronation since the major surveying trips of Bridger, Cordall, Matthews, Grant and Tickell in 1956/57.

However, during the winter of 1969 two pairs of Fids independently dreamt of climbing the beautiful but distant Sandefjord Peaks. After some consideration it was decided it would be safer and more practical if we combined forces and took a pyramid and mountain tent – with no dogs on base it would have to be man-hauling, of course. So it was that on 29 August, Martin “Cookie”Pinder, Eliot “Che” Wright, Dave “The Grin” Rinning and John “Percy” Edwards found ourselves being towed over the seaice by skidoo to our first camp near the refuge hut at Shingle Cove. The next day we set off on skis pulling a load of 875 lbs in true Scott/Shackleton fashion onto the Laws Glacier.

Before long we found we had to relay on anything other than a gentle incline – pulling half loads up and then going back to bring up the rest. The downhill sections were no easier as the sledge tended to run away with us in tow, and when we traversed slopes the sledge tended to capsize. Around Deacon Hill we came across the first huge crevasses and it was then that Dave’s experience of sledging at Adelaide became invaluable.

-

- Leaving base on 29/8/69 – a typical ‘manky’ day with gale force winds and rain. Eliot and John by the sledge and Mick Mickleburgh (chauffeur) by the skidoo.

- Dave & John at Shingle Cove on a -20 degC day having brought sledge and rations over to Coronation by skidoo. Shingle Hut & Glacier are behind.

- The Laws Glacier camp with the 1st sledge load ready for the haul up to Coldblow Col; Brisbane Height behind.

- Breaking camp after the first pull up to Coldblow Col which can be seen to the west with Echo Mountain looming above it.

- We all take a breather, and photographs of course, on the way to Cockscomb Buttress. The West Face and Ridge of Echo Mountain is behind John (taking a photograph), Dave (still attached to the sledge) & Eliot (behind the sledge)

- On our way northwards across the ‘Badlands’, with Dave out in front on the long rope probing for crevasses. On the left is Worswick Hill and on the right are the icefalls from the Brisbane Heights.

- Our first view of the north coast of Coronation Island looking down into Bridger Bay. Early evening shadows and large crevasses: there is one running across the photograph just beyond the ski sticks only visible as a slight depression in the snow.

- The view south to Cleft Point and the coastal icefalls into the Norway Bight. Eliot with the sledge.

It was now clear that there were actually four Sandefjord peaks running N/S but we still had to get onto the Pomona Plateau first. On the steep descent from Deacon Hill we lost control of the sledge completely and it careered off down-hill, fortunately coming to a stop at a flat col rather than veering off down the crevassed slopes to the north or south coasts. The Tilley lamp got smashed so it would have to be candle light from now on but that didn’t matter too much as we already felt we were low on paraffin!

Nine days after setting off we were camped at the foot of the peaks and on 6 September (Che’s birthday) we set off, first on skis and then on foot, and managed to reach the top of the highest two summits. We told base of our success by morse that night and, after two days lying-up waiting for the NE gale to blow itself out, we set off again and climbed the remaining two. Four virgin summits! What joy!! It didn’t matter to us that they were only around 2000 feet high.

-

- Looking westwards across Deacon Hill to the Pomona Plateau with 2 southernmost Sandefjord Peaks just visible. One of many crevasses runs across the picture and, beyond it, David and John are visible as a black speck as they return from a recce to the top of Deacon Hill. The route onto the plateau lay over the top of the hill and up between the two snow ridges on the slope behind, these being the edges of large crevasses.

- John, Martin and Dave cleaning skis at the furthest west camp site on the Pomona Plateau before setting off to climb two of the Sandefjord Peaks. The outward route from Signy along the foot of the Brisbane Heights has been marked in.

- Dave, Eliot & Martin with the 2nd highest Sandefjord Peak (1,934 ft) behind. Although the climb was not much more than a simple walk, there seemed more crevasses than on the other 3 peaks and our attempt to return to the tents by a different route proved too risky.

- Rime accumulation on tents and skis after a two day lie-up. The route taken up the highest Sandefjord Peak (2,083 ft) is shown.

- John making an ice ob. from the top of the northernmost Sandefjord Peak, with the jagged Larsen Islands behind. The peak is at the end of the ridge and there is a sheer 1,500 ft drop at the edge, beyond which Monroe Island is partly visible.

- The straightforward route to the top of the northernmost Sandefjord Peak (1,780 ft). Eliot & Martin are preparing to leave for our attempt on the southernmost and last remaining unclimbed Sandefjord Peak.

- Eliot & Martin waiting their turn to climb to the crest of the ridge leading to the southernmost Sandefjiord Peak (1,862 ft). Dave is out of sight in a dip below the start of the indicated route to the summit.

- Martin skiing past the highest Sandejord’s eastern face, wrinkled with many large rime bosses, en route to the southernmost peak.

- Martin belaying Dave on the final section of the ridge – a wall of unstable “honeycomb” rime leading to the summit with magnificent exposure either side of the ridge. We set up a fixed rope and all visited the small summit, completing our 4th “first ascent” on Coronation.

- The view from the vertiginous summit eastwards along the weird rime-bossed ridge, with Meier Point and Gosling Islands visible to the right of it. In the distance stretches the whole of the south coast of Coronation Island. The peaks of Signy are in the top right, poking through a sea of cloud.

We then set off back to base, minus the radio as this had suddenly packed up, filling the tent with acrid fumes. The sudden cessation of communication caused some concern on base, as we had planned for a 14-day trip but still hadn’t returned after three weeks even though the weather appeared fine over most of western Coronation. We did not know this, however, as high winds funnelling from the north had caused cloud formation at the foot of Deacon Hill where we were camped so we spent six days lying-up in a whiteout!

Eventually we got going, in less than ideal conditions, and had a narrow escape when the bridge of a large crevasse caved in as our skis crossed it. Fortunately we managed to halt the sledge before it slid into the hole and possibly pulled us in with it. On our final day we covered 15 miles and returned to be greeted as heroes by our colleagues on base. After 24 days (13 of them spent lying up) and 67 miles we were tired, dirty & smelly but ever so happy that we had achieved our objective and completed a journey that had not been done before. As far as I’m aware it hasn’t been repeated since and this is very unlikely in the foreseeable future now that Signy is a summer-only base.

-

- Another entry in the diary of Chaiman Che, who’s cornered the days food again! “Did we have any muesli yesterday?”

- The photo that proves there are four Sandefjord Peaks! John & Dave dismantle the mountain tent after 6 days lying-up in cloud & high winds below Deacon Hill. Little did we know that this was a very local phenomenon and the rest of Pomona & Signy were clear and sunny! The jagged Sandfjord ridge stands out clear above Parpen Crags and the southern part of the Pomona Plateau.

- “That hole wasn’t there a moment ago!” The hidden crevasse that opened up when Dave & John skied over it whilst crossing the “Badlands” on the final day of sledging. Fortunately Eliot & Martin were able to stop themselves, and the sledge, before the edge of the crevasse, although 2 feet of the sledge (ironically the part with the crevasse rescue gear in it!) ended up overhanging the hole. Brisbane Heights rise up to our east.

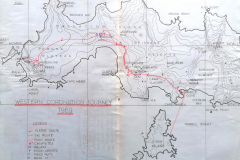

- The route map from our Base travel report K/1969/H.

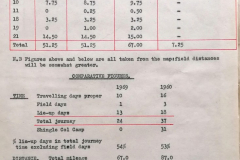

- Table of our daily mileages. We did not really get anywhere fast (except heading home!)

Click on the links below to get to a relevant page or use the pull down menu under the Stories tab.

| Timeline | 1950’s | 1980′s |

| Pre – 1947 | 1960’s | 1990’s |

| 1947-49 | 1970’s | 2000 on |