Signy Science

The 1970’s saw the emergence of longer term terrestrial, freshwater and marine research programmes with research field assistants operating long term monitoring programmes that provided background data to support individual research projects. The terrestrial section set up the SIRS (Signy Island Research Site) monitoring sites to study moss communities in dry (SIRS 1) and wet (SIRS 2) peat environments. The freshwater section began regular monitoring of a number of lakes of different nutrient status and twice a year sampled all 14 lakes on the island. The marine programme set up its ZM23 monitoring programme on a transect out of the Cove into Borge Bay and also did surveys of bird colonies, seal breeding success and an annual seal count.

The arrival of the workboat ‘Serolis” in the mid-70’s, together with more inflatables provided much greater capability to safely access the entire coast of Signy and the southern coast of Coronation Island. It also provided the ability, with the workboat’s A-frame, to haul nets and potentially take sediment samples, though the latter, in practice, proved problematic and was not used beyond initial trials.

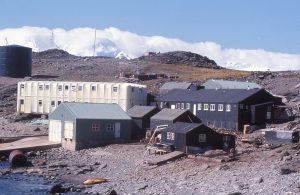

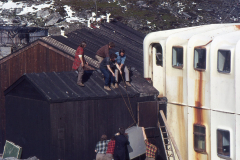

L-R: New Genny Shed under construction 1975; New Generators coming ashore (G.Picken); Installing a fuel tank for new Aga ovens.

L-R: New Workboat -Serolis (D. Allsop); Signy in summer; Signy in winter (G. Picken)

Around the Island on the Sea-Ice

Cynan Ellis-Evans

Sea-ice at Signy is a decidedly moveable feast and this has been particularly true in more recent years. My first winter (1976) was a reasonably good ice year with a number of trips to Coronation, whereas in 1977 we had one of the worst sea-ice winters of the Signy wintering base period. The sea-ice came and went a number of times and, although there was great interest in travelling to Coronation, only one group made it across and they then had a rather difficult time crossing back to Signy.

During that first ‘76 winter, Jim Cullimore (cook), David Wynn-Williams (microbiologist) and myself were at the bar one evening discussing the variability of sea-ice around the island and its rapid changes. There had already been a couple of minor incidents with people crossing the sea-ice, even in what was considered a good sea-ice winter. Nevertheless we felt that the sea-ice did look good away from the shore on both the east and west coast. With the weekend coming up we somehow came around to wondering if it was possible, using skis, to circumnavigate Signy entirely on sea-ice and, ideally, complete this in a single day. Having been introduced to cross-country skiing in Norway some years earlier I was optimistic, particularly as the availability of field huts around the coastline meant that we had options to bail out at various points if the route became impassable or the weather changed.

Come Sunday, with Jim free from his culinary duties, we strapped on our skis in truly dingle weather and headed out early morning around Bernsten Point. We made good progress across the front of Paal Harbour but as we began rounding Gourlay Peninsula to ski down the south coast we started encountering a series of cracks running east-west in the sea-ice that were not visible from shore. We had to ski or leap over these cracks and weave a way around bergy bits embedded in the ice which made for very slow going. There seemed to be more solid looking ice further south and indeed we were able to comfortably ski outside the larger Oliphant Islands and through the Dove Channel. However, as we came around towards the front of the Mcleod Glacier it became apparent that a large amount of ice and small bergs had pushed in towards the shore along the entire front of the Glacier, piling up in various places and creating major obstacles for skiing. Cue a couple of hours of clambering over pressure ice and bergs, using crampons in places, whilst following a tortuous route along the front of the McLeod Glacier to avoid occaisonal patches of thin ice and open water. By this stage we were wondering if a circumnavigation in the day was really possible as time was passing.

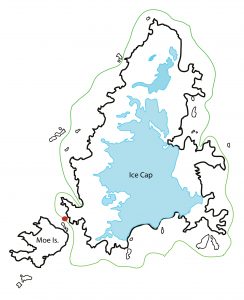

Circumnavigation route and site (red dot) of Jim Cullimore’s downfall

As we passed by Pandemonium Point the travel conditions started to ease somewhat. Moe Island and Mariholm now lay directly ahead of us. Despite some greyish looking ice towards the south of Mariholm it initially looked very tempting. Could we get round these islands as well? Moe Island (a Specially Protected Area) is rarely visited and Mariholm is very difficult to land on in summer so getting a closer look would be a good tick. However, we had not gone very far in a more south-easterly direction when the ice ahead began to look increasingly uncertain and, after some debate, discretion overcame curiosity and we beat a reluctant retreat.

We instead headed into the southern end of the Fyr Channel separating Moe Island from Signy and found sea-ice surface conditions markedly improving. We could finally make serious progress again on our skis and were all feeling much more upbeat. We were beginning to think we may have passed the worst when, out of the blue, Jim goes through the ice (marked on map) up to his arm-pits, skis and all. On either side of him Wynn and I were around 5 metres or so from him and on solid ice, but Jim had chanced on a substantial thin patch. Staying on our skis we pulled him out, though detaching his skis proved entertaining. He was, of course, somewhat wet and would soon be getting decidedly cold, but we were only a a short distance from Cummings Cove and its Bothy field hut, so we skied around Porteous Point into Cummings where we encountered DEM Pete Witty having a day out from Base. A brew later, we were able to leave Jim to warm up properly in the hut and for him to later return to Base with Pete whilst Wynn and I continued our circum-navigation as time was getting on and we were not even half way.

A week earlier, when I skidooed over the ice cap to sample one of my study lakes (then Lake 10, now Amos Lake) the west coast ice had been patchy in some places, though mainly passable near the shore. In contrast, as we skied out of Cummings Cove, a billiard table flat highway of solid sea-ice a quarter of a mile wide stretching up towards North Point and complete with diamond dust soon unfolded before us. Certainly the best cross country skiing conditions I ever experienced on Signy. With the sun beating down on us we had a rather warm time getting ourselves up the west coast inside Jebsen Rocks and past Foca Cove, despite the temptation of another brew at Foca Hut. However, by the time we had made it to Spindrift Rocks we were making such good time that we did stop off for a visit to the penguin rookery. Even the often unreliable ice conditions around North Point proved fairly straightforward and we were able to make good progress down the east coast arriving at base late afternoon feeling very pleased with our day’s work.

Postscript (Oct 2021) Despite some investigation of past base reports we were not aware at the time that anyone had circumnavigated the island before us. However, when I passed this article to Bob Burton he tells me that, in 1964, a team of Joe Sutherland (chippie) and John Noble (another cook!) had man-hauled (see above) around Signy on John’s week off. Their progress was apparently very slow until they depoted the tins of fruit and other goodies that Joe had secretly added to their haul! It seemed that we have to settle for having merely completed the fastest circumnavigation though it is of course possible that maybe someone else has scooped even that record.

Post-PostScript (Dec 2021): My suggestion at the end of the Postscript proved correct. It does indeed seem that even our claim of the fastest circumnavigation is in doubt. On reading the BASC Magazine No. 86 (Dec. 2021) I have come across a letter from Russell Thompson (BL, Signy 1961) where he details a very impressive circumnavigation, with a dog team, of both Signy and Moe Islands in winter 1961 which they completed in a day. Like us they had some hairy moments with dodgy sea-ice along the route where the dogs fortunately helped the party get back onto ‘terra firma”.

The Signy Thin Ice Race

Most Antarctic winter stations have their various sporting activities and so football, cricket, even golf, on ice are rather passé. However, the substantial scuba diving facilities at Signy allowed the establishment of the novel sport of thin ice racing. As the ice started to form on Factory Cove, early in the winter, the base commander would take to almost daily assessment of the developing ice cover. To the less well-informed this may seem an early sign of winter BC paranoia but second year fids recognised the imminent announcement of that winter’s Thin Ice Race. Regular checks were essential as sea-ice that was easily walkable would make a mockery of the event whilst sea-ice too thin would simply be a lumpy swimming event. What was ideally needed was ice across most of the cove that could hold your weight for at least a very few seconds at a time.

A course could then be established by the BC, an activity which, to his chagrin, often provided excellent entertainment for the rest of the base ahead of the main event. The route would involve circumnavigating various markers on the ice and more solid points, such as a rock or grounded bergy bit, that had to be touched en route. Such points inevitably had associated tide cracks or particularly thin ice to thwart the competitors in this endeavour.

All the competitors donned a wet suit but there were then no restrictions as to what else might be worn on top of the neoprene as the photographs illustrate. The race began with an alcoholic toast on the Plan and then it would be every man for himself. Everyone goes through the ice at some point and indeed some of the heavier members of the base struggled to get much beyond the tide cracks around the shoreline as getting out of the water onto more solid ice was an exhausting business. In some cases, competitors would have to just wallow in a hole until they were rescued at the end of the race.

Left – The competitors, Centre – En route (both G. Picken), Right – 1980’s version, same result! (M. Sanders)

The lighter competitors, and especially those with more knowledge of thin ice, could look for areas where ice plates overlapped giving a slightly more stable platform, but even then some of the more bizarre accoutrements (medical stretchers, superhero costumes) could stymie their efforts to make progress. Oh, for a set of ice screws as you try yet again to pull your knackered body up onto the ice! The leading competitors could be (and were) ambushed by one or more of their opponents on the way back to the finish, but equally they could take great satisfaction in breaking ice around floundering colleagues before (and after) reaching the shore to claim victory.

In the 1976 winter, diving officer (and later well-known wildlife cameraman) Doug Allen was the winner and he later went on to “out” this unique event in “She” magazine – a copy of Dougie’s excellent article featured in the 2018 Reunion exhibition.

The Visits of the San Martin and the Hero to Signy

In November 1976 we were clearing up after a very busy winter and getting organised for first Bransfield relief which was due in 2-3 weeks’ time. David Wynn-Williams and I ad been tasked with digging out a route through deep snowpack at the top end of the Plan when we were surprised by the sight of an inflatable dinghy with an Argentinian crew motoring into Factory Cove and son pulling up on the slip. Turned out that they were crew members of the A.R.A. General San Martin which was a sizeable naval vessel that supported the Argentinian Antarctic programme at that time and had just visited the Orcadas station on Laurie Island. With the political situation it did not make a habit of visiting British stations so it would have not been that well known to Fids.

The San Martin had apparently(!) attempted to call up Signy on various radio channels without success, including the international maritime channel (which in fact we always monitored). They seemed surprised to find us in residence as they had curiously assumed that the station had been abandoned. We found this rather unlikely as we had been playing darts over the radio with the Argentinians at Orcadas during the winter and indeed they owed us a quantity of beer. The ship having just visited Orcadas we were rather disappointed to find the beer was not on board!

Whatever, they invited us onto the ship though I do not remember much about the tour of the ship – typical naval vessel with an enormous complement as they had marines and helicopter air crew as well as the ship’s crew. What I do recall was us being fed Argentinian beef steaks with an egg on top. They were of course showing off the superior quality of their beef and given that our winter fare was largely frozen chicken and tinned meat we were very pleased to take what they offered. However, when we were offered seconds I recall us fids asking just for eggs (which we had not seen all winter, other than the odd penguin egg) which bemused them and left their stewards somewhat deflated.

The San Martin was an ageing naval vessel and seemed not that well maintained. This was exemplified on the trip back to base in a launch when the tiller arm came off its mounting in the launch which then veered drunkenly towards the rocks near Bernsten Point as the helmsman scrambled around looking for the missing bolt, saying “This happens all the time – it is not a problem”.

Colin Maiden, the winter BC, invited the Argentinians onto the base and they duly sent a deputation ashore in the launch. It was pointed out that there would be an exceptional low tide that day and suggested they put their launch out on our workboat’s mooring. However, they simply left it at the end of the jetty with two seamen standing guard at bow and stern, whilst the rest of the party undertook a lengthy tour of the base. Predictably, the launch was soon completely high and dry.

When the tours finished the groups came back to find themselves stranded and a genuine farce ensued. There were officers ashore from the army, navy and air force representation and each tried to take command of the situation, all shouting into their own individual VHF radios. A small landing craft was brought in but could not get close due to the rocks. There was much inept throwing of lines from the launch and when they did get the tow line to the landing craft it was, not surprisingly, a total failure as the launch was still largely out of the water.

In the meantime, Fids were up on high points and hanging out of windows photographing all this, to the great embarrassment of the Argentinian officers. The latter, on finding that the radios they had been shouting into were going flat, headed to the radio shack where they all three then seemed to try to shout into the mic simultaneously whilst Radio Op Danny Downey attempted to keep order. Eventually the tide came in, the launch re-floated and a decidedly embarrassed group of Argentinians quickly headed back to the ship, no doubt anticipating a difficult conversation with the captain.As an addendum, there was a major news story back in 2007, when a major fire broke out on the A.R.A. Admirante Irizar, a very impressive Finnish-designed icebreaker, which had replaced the San Martin in the 1990’s, whilst it was sailing in the Peninsula area. The crew had to take to the lifeboats and were fortunately rescued by fishing vessels who were in the area. The extensively damaged Irizar was recovered to Argentina but the enormous repair bill and Argentinian politics meant it took over 10 years to do the rebuild and she only finally got back to sea in 2017.

Left – ARA Irizar in happier times, Centre – Irizar after the fire, Right – RV Hero

We had another visiting vessel later that summer of 1977 when the US research vessel R.V. Hero dropped by whilst supporting a geological programme in the South Orkney Islands. The Hero was launched in 1968 and was named after the sloop that Nathaniel Palmer was using when he first sighted Antarctica. She was a heavily-built 125 ft long wooden trawler that for nearly two decades (1968 – 1984) served as the National Science Foundation’s research vessel in Antarctica, working particularly out of Palmer Station. Hero resembled a classic East Coast side rig trawler but she was designed for ice work and so her sides and keel were clad in exceptionally hard tropical greenheart wood overlying thick oak boards and a very heavy duty frame. Powered by twin diesel engines she was rigged as a ketch which gave her greater stability and also allowed silent running, which was highly desirable for some aspects of marine research. In addition, she had a variety of winches, several small laboratories and a work boat to support underwater research.

There was one amusing moment I recall during her visit in 1977. Several of the Hero’s complement came ashore and walked into the Signy lounge where fids were chatting around the bar waiting for news on what was to happen next during the visit. The visitors were clad in hats and heavy outdoor clothing so they were initially difficult to distinguish, but two were clearly very large figures sitting either side of a much slighter individual. The Fids looked at the visitors for a moment and then boatman Nick Cox whispers “I think the one in the middle is a woman!” All the Fids seemed to simultaneously take a step back in shock – it had been a long winter. An awkward impasse of several seconds followed before the summer BC, John Hall, walked into the room to talk with the visitors and we quickly realized that the woman was Dr. Janet Thomson, wife of Mike Thomson, and a member of the BAS geology group. She had very close links with geologists in the US Antarctic Programme and was collaborating with them on a geological survey of the South Orkney Islands.

The Hero was a real novelty for us, a delight to see with her sail up and could get into all sorts of shallow locations that were inaccessible to the larger US research vessels. After her final season she was acquired by a non-profit foundation aiming to operate her as a museum ship but funding ran out and she then went through several owners who tried and failed to renovate her. She ended her days in Washington State where, sadly, she sank at her dock in March 2017.

Some articles from Gordon Picken (winters 1975,1976)

The Signy Zotter

Gordon Picken (article from the 60th Anniversary reunion magazine)

My programme of research was to study the gastropod snails that lived in the shallow water around Signy Island. One problem was: how do you collect small animals when you are wearing thick diving gloves and so bloody cold that your thumbs and fingers don’t work? Remember, this was in the days of wetsuits rather than the modern dry suits.

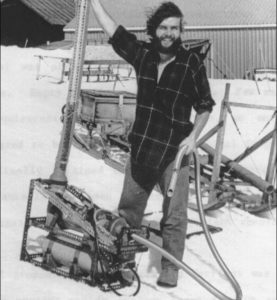

Martin White suggested that I should build an underwater ‘hoover’ for collecting the snails that lived exclusively among the seaweeds and rocks. I found a design for an air-lift suction device and set about getting it built. The result was the ‘zotter’, cleverly constructed by Doug Bone. It was used on about 250 dives at Signy from 1974-77 and worked perfectly. Without it, we would never have been able to collect and study so many fascinating ‘ghastliepods’.

We dived every month, using the zotter to take quantitative samples by hoovering up all the snails within a metal quadrat placed at pre-determined intervals along the transect. It was cold work, especially for the‘buddy’ (usually the Diving Officer) who waited patiently for about 20 minutes holding the zotter’s uplift pipe while I vacuumed the seabed.

Using this wonderful machine we collected thousands of snails, most of them small and drab and really difficult to see. What we had not expected, however, was that during the winter and autumn, under the sea ice, the zotter would collect hundreds of juvenile snails that had just hatched from eggs. It was hardly possible to see these tiny animals. But after each dive, when the mesh bag from the zotter was emptied out into a tray of seawater, a transformation took place. Small dark specks gradually grew tentacles and a head, and soon the seaweed fragments and rock chips in the tray were covered with hundreds of beautiful, miniscule snails. They had been laid as eggs 6-8 months before and had hatched in the depths of winter. After two years, we had found 51 species of snails around Signy that reproduced in this way. The eggs develop very slowly and, instead of producing a larva that swims, each egg produces a tiny, perfectly formed snail that crawls out of the egg directly onto the seabed.

The zotter was still going strong in 1977 when it was passed on to Richard Luxmoore for collecting Serolis (the isopod, not the boat). When Richard first arrived on Signy, I knew straight away that he was the man for wrestling with the zotter’s uplift pipe and hoovering hose: he was carrying, if not actually playing, a set of bagpipes!

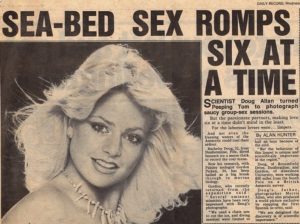

Signy Sex Romps

Gordon Picken

Author’s warning: The language and image in the newspaper article referred to in this piece may be upsetting. Readers are reminded that it was published a very long time ago, in another era. Please send any complaints to D. Allan Esq.

‘The benefit of going South for two years’, they said, ‘is that you have three summers for your biological studies. In the first, you learn the basics and get your programme up and running; in the second, you might actually learn something new; and in the third, you can check if your results are real’. Many Antarctic processes are slow and can be observed over long periods of time. Long-term observations month after month can sometimes reveal what’s going on much better than just a single snap-shot sample. And so it transpired for my studies of the ecology of marine prosobranch gastropods (i.e. snails) in the highly seasonal marine environment around Signy.

The shallow rocky region of the Antarctic coastline, from the ice foot down to about 20-30m, is difficult to sample using traditional grabs or trawls from large expedition vessels. But the advent of scuba diving meant that it could now be explored in great detail. When diving started at Signy it opened up a whole new world for marine biologists. I studied all the gastropods found down to about 20m, including the common Antarctic limpet Nacella concinna. This limpet is found all around the continent and over a great depth range, from intertidal to several 100s of metres. For most of the year, it lives a solitary existence, grazing over the rocks and seaweeds. At Signy, it had been studied in the 1960s by Tony Walker, who showed that it migrated down the seabed in winter to retreat below the level of the sea ice.

My main sampling site was Billie Rocks, easily accessible from Base in summer and winter, but in more open water and away from any human influences and disturbances. It was here in the summer of 1975/76 (Dive 114, 30 November) that Jon Brook and I saw limpets apparently mating. We saw several “stacks” of limpets, with 4-7 adults balanced on top of each other. This was an unusual and hitherto unreported behaviour. We went back a couple of days later but found nothing, and despite searching for the rest of summer we did not see any more stacks. Whatever was going on here was quick and short-lived.

This was a tantalising glimpse of something new, perhaps. Were these limpets behaving like the European species Crepidula, where males and females stack alternately for mating? In the summer of 1976/77, Doug Allan and I carried out a more intensive campaign of monitoring. From late November we dived nearly every day, determined not to miss the start of the mating season. We visited Billie Rocks, Porny Rock, Shallow Bay, Cam Rock, Mirounga, Small Rock, Bernsten Point and the head of Factory Cove. Our persistence paid off when, on 4th December (Dive 231), we found several stacks of limpets at Billie Rocks. The adults were precariously perched on each other (it was a very calm day, for Signy), and in Doug’s beautiful photographs the shower of brown eggs and the skeins of white sperm can be clearly seen. These animals were definitely mating! We collected the animals in individual numbered jars, and in the lab found that they had not stacked up with males on females alternately. We searched throughout December but did not find any more stacks that summer. These were clearly very brief encounters!

|

|

L-R: Stacked limpets mating at Billie Rocks. (©Doug Allan); Press take on the research (©Daily Record, 1984).

This was indeed an interesting new discovery. Doug and I wrote it up and it was published in Nature. However, it received much greater attention about a year later when, through Doug’s connections with the world of journalism, it made the headlines in the Daily Record. The power of the Press!

References:

Picken, G.B. and Allan, D. (1983.) Unique limpet spawning behaviour. Nature, 305, p 472.

Daily Record, Wednesday March 7th 1984.

Signy, Signyensis

Gordon Picken

There is an awful lot of Antarctic biology on Signy Island. Ron Lewis-Smith nailed it in his lovely article “In Praise of Signy” (BAS Club Magazine No.80) when he wrote:

“..Signy has the longest track record of any Antarctic station for continuous biological research, where pioneering fundamental ecological and physiological studies have greatly advanced our understanding of the ecosystems and biota of the seventh continent, yet concentrated in a tiny fragment of it”.

“This spectacular landscape abounds with wildlife like no other of comparable area within Antarctica. Fourteen of Antarctica’s 18 breeding bird species breed on Signy…Four of the continent’s six seal species are abundant on the shorelines…Besides the two native Antarctic flowering plants, the readily visible vegetation (mosses, liverworts and lichens) comprises about 70% of the entire macroflora of Antarctica. Several of these are island endemics…Similarly, Signy has a diverse microfauna comprising predominantly springtails and mites…The island’s inshore marine fauna is equally remarkable, diverse, colourful and, in some cases, unique”.

With all this science-ing going on, one might expect that Signy would have leant its name to several new species of plants and animals. In Linnean nomenclature, the species name often refers to the place where the organism was first found. In the case of Signy, that would be Signyensis (sometimes Signeyensis) or maybe Signyana or Signeyana.

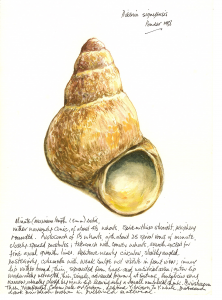

I have done a quick search; on Google. (I know, sorry, call yourself a scientist?). So this is at best preliminary, and I apologise for any Signy-named species which I have not found in this briefest of searches. Surprisingly, I found only six species named for Signy. In chronological order they are:

Chlanidota signeyana, Powell 1951 (marine gastropod)

Enchodelus signeyensis Loof 1975, (now Enchodeloides signeyensis) (nematode).

(Enchodelus sp. described by Vaughan Spaull in 1973, then later named signeyensis by Loof)

Notoficula signeyensis, Oliver 1983 (marine gastropod)

Pickenia signyensis, Ponder 1983 (marine gastropod)

Vahlkampfia signyensis, Garstecki & De Jonckheere 2005 (amoeba)

Myriospora signyensis, Purvis, Fedez.Brim, Westb & Wedin 2018 (lichen)

Although I collected the gastropods Notoficula and Pickenia (see “The Signy Zotter”), they were named by recognised taxonomists. For my part, this is an important distinction. With the zotter, I was able to collect hundreds of tiny snails from the shallow rocky zone that extends from low tide to about 20m – a zone which had been poorly sampled in historic expeditions of the “heroic” age. While zottering, I only saw the big specimens like limpets (Nacella concinna, see “Sex Romps in Antarctica”) or the medium-sized but bright white Margarella antarctica. When I emptied my bags back in the wet lab, the white trays appeared to be covered only by a layer of gravel and grit, of various shades of grey and black, with bits of seaweed and other detritus. It was delightful and miraculous to wait and watch while these tiny pieces of grit came to life, cautiously extending a tentacle, a head, a foot, and then begin to crawl around the tray as if nothing had happened.

So, I may have collected the snails, even perhaps in the cold of the old wet lab found them, but the experts identified and named them. Graham Oliver of the National Museum of Wales, and Winston Ponder of the Australian Museum named two of the new species after Signy, and Winston was kind enough to name a new genus Pickenia.

New snail P.signyensis

But before I could get too big-headed about this, I was brought down to earth by this birthday card, which, as you can see, highlighted some of the less flattering diagnostic features of this new genus. Who, me?

Lost and Found

Gordon Picken

Diving on Signy was hardly ever dull (well, maybe on some manky days with low vis, 25 knot breeze and choppy Borge Bay and boot boatman), and occasionally slightly terrifying. Unfortunately, after many routine dives, week-in and week-out, in a familiar area, a slight blasé feeling can creep in.

Dive 99 (!) (6th October 1975 since you ask) was such an instance. We had cut a dive hole at Billie Rocks, and then skidoo-ed out to move the transect (for the sampling of gastropods in the shallow sub-littoral, see “Signy Sex Romps”).

With Nansen sledge on plan, preparing for a winter dive

Even underwater, the old harpoon heads used to mark the transect are heavy to move, and we had a lot to relocate and then straighten up the line and its float markers. Time passed; 40 odd mins at 8-12m, in a wet suit, water temp about -1oC. Not too bad, and we were acclimatised to winter diving, but even so, inexorably, bodies began to get cold, vision began to close-down slightly.

Under the ice at the dive hole (©Doug Allan)

The job was completed and just in time as I, for one, was low on air. We started to move towards the shaft of light marking the dive hole; I was on the end of the safety line. Halfway back, finning in mid-water, I realised the line was snagged around a huge clump of seaweed on the bottom, well behind me. I decided to turn back and sort it out. I started to swim diagonally down to free the snagged line. At the same time, unseen by me, the line was being reeled in by the guys on the surface and the slack taken up.

Breathing became more difficult as my air ran out. I realised that I did not have enough air, or time, to swim across and down to the snagged line, and now there was no slack in the line for me to reach the dive hole. I reached for my diving knife, cut the line, dropped the knife and swam straight up to the underside of the 1m thick sea ice, thinking that my air might last a little longer if I swam at a shallower depth. With fins and neoprene-mitted hands I scrabbled along the face of the ice, definitely now sucking in the sides of my tank, gulping water, and, at one point, shouting for help (I know, underwater, but it’s kind of instinctive!). It seemed like a long time but was probably only a few minutes. My absence was noticed, help arrived, and I buddy-breathed back to the hole and onto the Nansen.

I had a couple of quiet days and then there was a five-day gale, but I got back into the water later that month to resume the sampling, chastened, and a bit wiser. Stupidly, I had got myself into a bad situation through cockiness and inexperience and was grateful to my buddies for rescuing me.

In the course of sampling we swam over the whole of the study area at Billie Rocks at least once a month. It was rugged and rocky, with a profuse cover of seaweeds and my knife was lost. However seven months later (Dive 157, 18th May 1976), Doug Allan, Jon Brook and I were again sampling the Billie transect when Jon found the knife! Just lying there on the seabed. I have kept it safe ever since; the knife that saved my life.

The trusty diver’s knife

Signy Leopard Seal

Gordon Picken

It was a calm summer’s day on Signy Island (19th February 1975). The flat water of Borge Bay reflected the flat grey sky above. There was hardly a breath of wind. Tiny waves lapped against the rusty boiler half-buried in the shingle. Even the few remaining ellies were listless. It was very quiet.

Into the bay drifted a single, small bergy bit carrying a solitary, gonking, Leopard seal. At the head of Factory Cove it pirouetted on an unseen current, and came to a stop.

And, without any sort of signal, from all their different haunts and hidey-holes, almost the entire personnel on Signy base emerged, cameras at the ready. This was not the first seal they had seen. But it was an unexpected chance to get a good close-up look at a Leopard seal. It was perfectly positioned to view from the plan; it was, you could say, well within range. Telephoto lenses were adjusted, shutters clicked, Kodak shares rose.

A later (1977) encounter with a leopard seal on the Signy plan. L-r: Ian Reston, John Caldwell, Julian Priddle, Bernard Despin (visiting French scientist), Pete Ward, Gordon Picken, Jon Brook, Dave Rootes, John Cullimore, and Bill Rogers. Photo © Unknown FID, possibly Richard Anthony. Click on image to enlargeMany good shots were taken that afternoon in 1975 but the keenest eye and the most dramatic shot was Nigel Bonner’s, the Head of Life Sciences, who was visiting that summer. Herb Dartnall (the new BC) had obtained permission from Dick Laws for a leopard seal specimen to be taken. This animal was unusual because it had a strangely twisted skull. Nigel settled himself prone right at the end of the jetty and killed the seal cleanly with a single shot of the base’s .303 rifle. It did not move an inch; the black blood ran over the white ice and into the sea. Howard Bissell took Nigel over to the bergy bit in Mwwhh, and they bled it there before towing it back to the plan.

L-R: Nigel Bonner and the Leopard Seal; Magnificent head of the Leopard Seal; Crooked skull of Leopard Seal (©Dave Friese-Green)

This lovely creature served many purposes; Herb took the eyes; Neil Tappin took blood and spinal samples, Ian Rabarts took the skin and Nigel took the skull. We must surely have eaten some of its strong, dark meat, but I have no record of this. I took the pectoral flippers (later to be made into a mid-winter present), someone took the tail flippers, and the capies and skuas took the rest. The head was boiled down and the twisted skull cleaned and photographed by Dave Friese-Green.

I hope the skull was of some use and is on display somewhere. The Latin name of the Leopard seal is Hydrurga leptonyx. The generic name hydrurga can be translated as “water worker”, which is where I wished it had stayed.

Click on the links below to get to a relevant page or use the pull down menu under the Stories tab.

| Timeline | 1950’s | 1980′s |

| Pre – 1947 | 1960’s | 1990’s |

| 1947-49 | 1970’s | 2000 on |